CHARLOTTE, N.C. -- Are Charter schools fostering segregation in Charlotte-Mecklenburg public schools?

According to a new study released by the Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles at UCLA with researchers at UNC Charlotte, the answer is yes.

"Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools were once the nation's bellwether for successful desegregation. Today, the district exemplifies how charter schools can impede districts' efforts to resist resegregation,” said Roslyn Arlin Mickelson, UNC Charlotte’s Chancellor’s Professor and professor of sociology, public policy and women’s and gender studies at UNC Charlotte.

“This research has important implications not only for schools and communities in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg region but for the national debate over the growth and role of charter schools in our nation’s education system,” Mickelson said.

In Mecklenburg County, there are 170 public schools within the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School system and 111 combined private (85) or charter (26) schools. Researchers say roughly 23 percent of families in the county are choosing a private, charter, or home school option over public.

Charter schools are tuition free, but not all offer free meals or transportation, which limits who is able to attend one.

“Evidence is very, very clear in the state of North Carolina and in Mecklenburg County. We see that charters are increasingly drawing the most academically able, many prosperous families, whites,” said Mickelson.

“Only people who can take their kids and have the time and have the vehicle can take their children to these charters, and that limits the population.”

At the opposite end of the spectrum are public schools within CMS. For example, the report found: “District enrollment is 40% black, 29% white, 23% Hispanic, and 6% Asian. And because of the close correlation between race and SES in Mecklenburg County, in the 76 schools where all students qualify for free lunch, almost 87% of students are black and/or Latino.”

Mickelson believes charter can be part of the solution if they put diversity first.

“Making sure that it’s part and parcel of one of the goals of every charter school in the way in which it operates and recruits and the instruction that it gives,” said Mickelson.

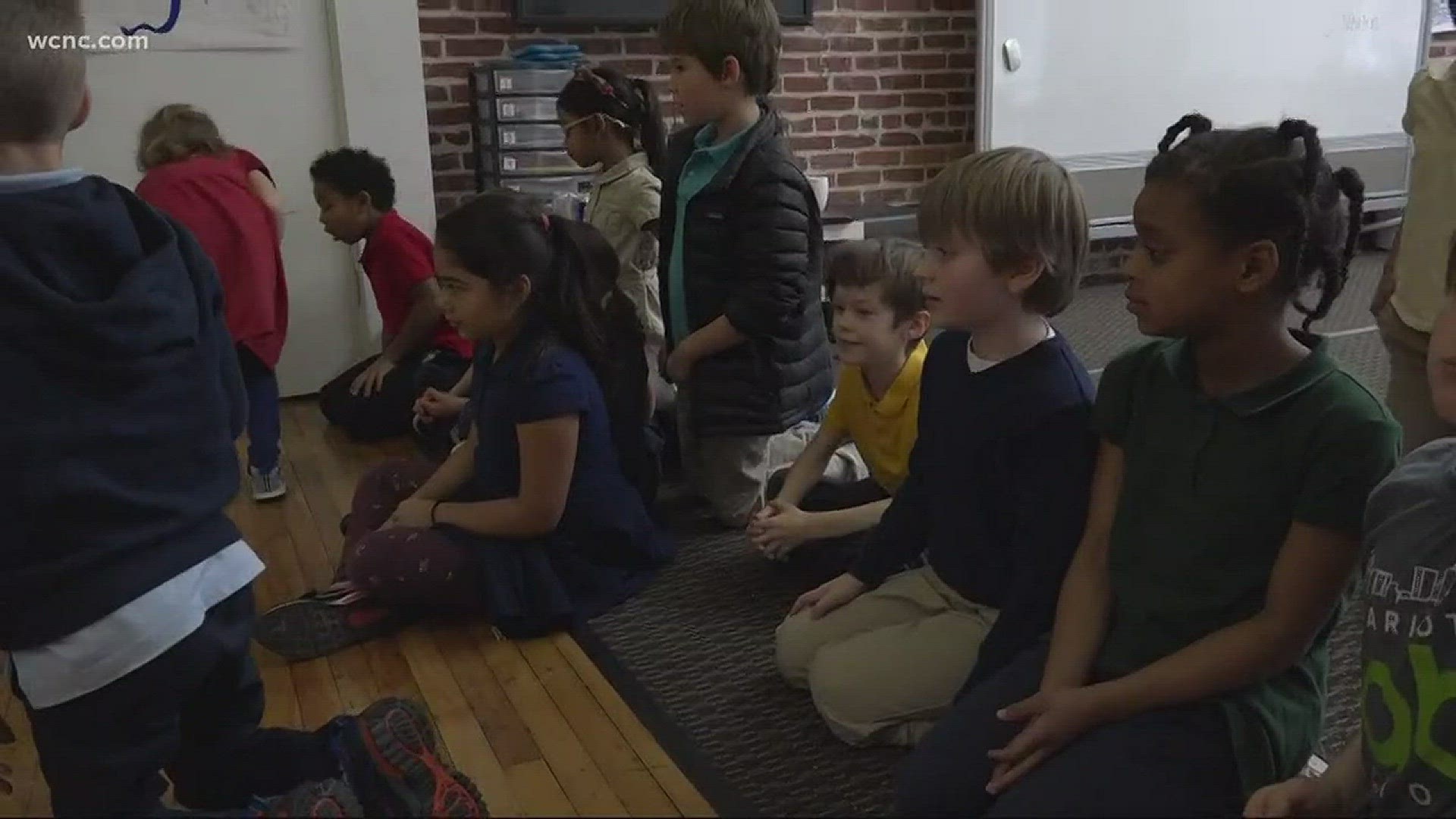

One Mecklenburg County charter school who is already doing so is Charlotte Lab School in uptown, serving 530 students, grades K-6.

“I don’t think going to school in places that are segregated will prepare our students sufficiently into the world in which they graduate,” said Mary Moss, the school’s co-founder and executive director.

Moss opened the school in 2013 after evaluating school offerings for her two children.

“I wanted an environment that would look at my child as more than a test score and would look at my child as a whole human being,” said Moss.

But equally important to Moss was diversity. So when Charlotte Lab opened, it received permission from state leaders to become just the fourth charter school in the state to have what’s called a ’weighted’ lottery. Because of it, the school is now able to reserve spots for students of low socio-economic status.

“Over the next several years we will go from about 20 percent of our students who qualify for free and reduced lunch to about 40 percent,” said Moss.

Moss admits charters have historically been part of the problem but believes, now more than ever, charter schools have an opportunity and obligation to be part of the solution.

“It’s definitely important that students get to go to school together, to learn alongside and from students that have different experiences than they do.” Moss said demand to gain entry into Charlotte Lab shows parents and families are willing to put to their children in socioeconomically and racially diverse schools.

“Last year we ended up with over 1,400 applications for probably fewer than 200 seats,” said Moss.

To help desegregate public schools within CMS, the school system implemented phases of a student assignment plan.

The new assignment plan will affect approximately 7,000 students, or less than 5% of the district's 147,000 students, and UNCC researchers said the changes only modestly shift concentrations of poverty.

The UNCC report also stated: “Because 2016 growth in charter enrollment surpassed traditional public school growth, Mecklenburg County Commissioners expressed their reluctance to fund new schools, improve existing facilities, or generally invest in public education if CMS student populations are not growing or even declining.”

Mickelson believes it’s now up to policymakers and citizens to think and decide how they want to deal with the growing problem.

“The horse is out of the barn. They’re here, and so we need to incorporate their strengths into the public system and harness and reform their weaknesses,” said Mickelson.