Asian Pacific American Heritage Month: Asian AND American

May is Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month.

May is Asian/Pacific American Heritage Month, which looks to celebrate Asians and Pacific Islanders throughout the United States.

In honor of that, WCNC Charlotte's parent company TEGNA put forth a series of stories about Asians and Pacific Islanders called "Asian AND American." The full special can be watched on WCNC's Roku and Fire apps as well as on our YouTube channel or embedded in the story below.

HOW TO WATCH WCNC Charlotte on-demand

History of Asian racism, violence

The attacks that killed eight people at three spas in or around Atlanta in mid-March helped further ignite a nationwide movement to not only stop hate against the Asian American Pacific Islander community but raise awareness about decades of unfair and blatantly racist acts.

Six of the victims from the spa shootings were of Asian descent. While the pandemic and anti-Asian rhetoric helped fuel numerous assaults, harassment and discrimination since March last year, the killings have become the latest tragedy in more than 150 years of racist and violent history in the country.

To understand the struggle to adapt in the U.S., look no further than Gordon Quan, a leading immigration attorney based in Houston, Texas. The American journey for his family began when his grandfather, a successful businessman in China, fled after being targeted by emerging communists in the early 1900s.

A warrant was issued for his arrest because he was considered a capitalist. His exodus took him to Mexico and eventually the U.S. where in San Antonio, Chinese residents were not permitted to buy a home. The Quans moved to Houston, where they opened a grocery store that had quarters behind it.

“I look with great pride, the courage my grandfather had coming to America,” Quan said.

The journey helped turn a young Gordon Quan into a nationally recognized immigration attorney. He knows better than most how hard ‘crossing to America’ has been for many groups. For Asian Americans, it was marked by the country’s first immigration ban based on race in the 1800s.

It can be traced back as far back as the Page Act of 1875, a restrictive federal immigration law that targeted Chinese women from entering the country.

The more recognizable Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 soon followed, which largely stopped Chinese men from immigrating and prevented those already in the U.S. from becoming naturalized citizens. States in the West pushed the law through by cutting a deal with states in the South that targeted another minority.

“The people of the South didn't care about the Chinese,” Quan explained. “There weren’t any Chinese there."

Quan said government officials in the South cared more about the Jim Crow Act and the number of African Americans being elected to Congress at the time.

Meanwhile, Chinese workers who made the trek to the West to work on the railroads were subsequently discharged. One of the major occupations they were able to engage in was mining. Due to economic circumstances, they were viewed as competitors for work and therefore, seen with a great deal of hatred by white immigrant workers and were subjected to ethnic cleansing.

Three years later, in 1885, an ongoing dispute over Chinese coal miners in Wyoming would become a bloodshed when they refused to join a strike for higher wages. In return, a mob of white coal miners attacked in what has become known as the Rock Springs Massacre.

RELATED: Georgia DA to seek death penalty, hate crime charges against 22-year-old spa shooting suspect

The mob killed 28 Chinese miners, injured others and burned dozens of homes. What was referred to as their Chinatown, members were driven out of their homes.

“White immigrant workers thought they were going to be displaced by these Chinese workers and decided to engage in vigilante justice,” the University of Colorado at Boulder Professor William Wei said. “They took matters into their hands and decided to arm themselves and drive them out of the community.”

The tension between cultures went beyond borders, like when the U.S. colonized the Philippines after winning the Spanish-American War in 1898. It took $20 million paid to Spain to seal the deal. Filipinos tried to fight for independence in what they called a revolution, but the U.S. government called it an insurrection.

Military officials uprooted indigenous tribesmen to showcase them at the 1904 World's Fair in Saint Louis.

“Filipinos were displayed in this world's fair as savages, as barbarians, almost like animals,” Jonathan Melegrito, former director of the National Federation of Filipino American Associations, said. “America was justifying going to the Philippines to civilize and Christianize the Filipinos.”

Young Filipinos eventually became farmers in California but under cheap pay and poor living conditions. In January 1930, a white mob attacked Filipino farmworkers for dancing with white women in Watsonville, California. That sparked similar attacks in other cities in Northern California.

“They [mobs] would create riots, assault Filipinos and they would attack and stalk them,” Melegrito added.

By World War II, China and the U.S. became allies in the fight against Japan. The legendary air unit, The Flying Tigers, was a high-profile example. The group initially had 311 members who were tasked with protecting China from the Japanese military. The Flying Tigers lasted for only a year.

Staff Sergeant Lewis Woo Yee, then an 18-year-old soldier, helped with the petition that ended the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1943. At 95 years old, Yee was eventually awarded a congressional gold medal.

“When you wear the uniform to serve your country, they pay attention to us, so in 1943, they did away with it,” Yee said.

However, WWII also brought out an uglier side to the country when 120,000 Japanese residents in the country, 70,000 of them U.S. citizens, were sent to internment camps for the duration of the water. Anti-Japanese worry rooted by the war and fear prompted the government to implement a severely drastic policy.

Meanwhile, about 33,000 Japanese served in the U.S. military and helped comprise the legendary 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The unit was the most highly decorated unit of the entire war.

Decades later, the Vietnam War sent 130,000 refugees to the U.S. after the fall of Saigon. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, many became shrimpers on the Gulf Coast. However, the competition triggered shootings, boat burnings along with assaults and intimidation by the Ku Klux Klan.

The shrimpers were terrorized despite seeking out a better life, but a Southern Poverty Law Center lawsuit helped put a stop to the threats and destruction.

In 1982, the murder of 27-year-old Vincent Chin outraged and galvanized the Asian American community. Chin was killed the night of his bachelor party in Detroit. Two white Chrysler autoworkers, Ronald Ebens and his 22-year-old stepson Michael Nitz, beat Chin to death with a baseball bat following an argument.

They were heard shouting racial slurs and saying, “It’s because of you little motherf*****s that we’re out of work.”

Chin was confused for being Japanese when he was in fact Chinese. In the trial, the men received a $3,000 fine but zero prison time. The case has often been attributed as a pivotal point for Asian American activism and civil rights engagement.

By Sept. 11, 2001, as the world was grieving, the terror attack also spawned even more hate, this time towards South Asians and people of Arab, Muslim and Middle Eastern descent. Bullying, harassment, racial profiling and vandalism at places of worship became a dark outcome. Fears following the attacks turned into blame against the community.

The first month after Sept. 11, there were more than 300 cases of violence and discrimination against Sikh Americans alone in the U.S. Nearly 20 years later, tracking hate crimes against the community continues to this day.

The model minority myth

The model minority myth – it’s a phrase familiar to many in the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community. It describes the flawed belief that all Asian Americans must be inherently successful, overachieving and law-abiding.

It’s something Helen Li, a Han Chinese American, had early exposure to while attending Chinese school on the weekends.

"I just remember having upperclassmen in Chinese school who were exceeding whether it was mathematics or all those extracurriculars. They would get into cool high schools and Ivy Leagues,” Li said. “Everyone around me ... would praise this person and I had no idea what that accomplishment meant. But what I did feel immediately was I somehow had to compare and be as good as these people.”

The pressure to be the best is instilled at a young age for many Asian Americans. “I think your racial identity stands out at a certain point. Over time, I started mistakenly thinking that what made me special was my ethnicity,” Li said.

Expectations can come from different places, like parents and friends. The term “model minority” itself stems from the apparent success of Japanese Americans in the U.S. following Japanese internment during World War II.

The seemingly “positive” stereotypes commonly associated with the model minority myth that are regarded as harmless have silenced the struggles of Asian Americans and given them a false sense of belonging.

“I think one of the most insidious things also is that we’re essentially being told that if we rise to the stereotype, then we will finally be seen,” said Jay Julio, a Filipino American. “We will be seen as white. And we can see of course that doesn’t happen.”

Under societal pressures to rise above the challenge, mental health is something that’s often ignored in the AAPI community. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders say they often feel discouraged to seek help because of the shame that’s often associated with it within the community.

“When I first started therapy, it was a huge struggle to get myself to go, to acknowledge that I needed the help,” said Amy Cao, a Chinese American.

The model minority myth also fails to acknowledge the wide variety of experiences of different Asian American communities, such as those who aren’t neurotypical.

“I did not realize growing up that I was neuroatypical. For one, I was very high achieving in school so it was swept under the rug and any symptom of ADHD and autism that I presented were cast away,” said Jay Julio. “They said, ‘Oh, this individual is really smart. They’re not like the others.’”

Julio said even when he did open up about his challenges and tried to find help, it wasn’t readily available to him.

“This side of me was never addressed by educational or medical institutions, and that’s something I think is deeply lacking… the way we provide healthcare to Asian Americans at the physical and mental level,” he said.

As anti-Asian hate crimes are on the rise, the reality is settling in that there is no “model minority” and there is no protection from discrimination, but communities are finally being heard.

“It’s being cautious. It’s being scared. But it’s also being proud. And also for the first time standing up for yourself,” Cao said.

Misidentified: Sikhs in America

Members of the world's fifth-largest religion stand out in America. But ask who Sikhs are and what they believe and studies show up to 70 percent of Americans won't be able to answer.

“On one hand we're hypervisible with our unique identity, our turbans, our beards,” said Simran Jeet Singh with the Sikh Coalition, a nonprofit founded after the Sept. 11 tragedies. “People definitely noticed me in an airport or on an airplane right? We're noticeable. And at the same time, people have no idea who we are.”

Today, there are approximately 30 million Sikhs worldwide. There are roughly a million Sikhs living in North America.

“Whenever I have to explain anyone who I am, what's my identity, I always tell them Sikhs used to be warriors,” said Deb Bhatia, founder of the nonprofit Sikhs of St. Louis.

Originating in the 15th century in the Northern region of India known as Punjab, Sikhism was established during a time where superstition and social inequity ruled the land.

Sikhism's founder, Guru Nanak, was born into a Hindu family. From a young age, he sought to establish a faith that considered all people- regardless of caste or gender-equal.

They called themselves Sikhs, which means 'students' in Sanskrit. The term ‘Guru’ translates to ‘teacher’. Over the course of two-and-a-half centuries, there were 10 Sikh Gurus. At the start of the 18th century, the Guruship was finally passed on by the tenth guru to the holy Sikh scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, which is now considered the living Guru by the followers of the Sikh faith.

“Sikhism is more about believing in humanity. Sikhism means that there is one God. We see a human race as one race,” said Bhatia.

Early in its history, Sikhs had to defend their faith against the Mughal empire and tyrannical rulers who persecuted religious minority groups.

That's when Sikhism’s tenth Guru, Guru Gobind Singh Ji, officially made the turban a symbol of the faith.

"Only Sikhs basically wear turbans,” said Vik Singh Saluja from Chesterfield, Missouri.

Vik and his wife, Pav Kaur Saluja, are Sikhs living in Chesterfield, Missouri.

They explain, other middle eastern and Asian cultures often wear head coverings that may look similar, but a Sikh’s turban is unique. It served in part, as a way to identify Sikh warriors during battle.

“When [Sikhs] were in war and they could not even identify who were the Hindus or the Muslims that they were fighting against, Guru Gobind Singh Ji actually turned and said, ‘The way that you will be identified is through your turban. And if anyone sees a man with a turban, they'll know that that's the person that you need to go to for protection,'” said Pav.

"Nothing has changed after so many years. You see a Sikh standing in the crowd and you need help, you go tell them and say, 'hey, man, I need help. You have to help me,'” said Bhatia.

Prior to the founding of Sikhism, turbans were worn by India’s upper-class and cultural elite. Kings and rulers once wore turbans. However, a core teaching of the Sikh faith is that all people are equal. In order to eliminate the class system associated with turbans, Guru Gobind Singh Ji declared every Sikh- man or woman- keep their hair uncut, and wear a turban. Other Purposes of the turban include protecting Sikhs' long unshorn hair and keeping it clean.

“We don't cut the hair because God has told us that we should keep our bodies the same way as we were gifted by the God,” said Bhatia. Not every Sikh wears a turban. Some choose to cut their hair for personal reasons.

Sikhism’s last Guru also rejected the caste system by giving all Sikhs the last names Singh (Lion) or Kaur (Princess). Today, you can find Sikhs use ‘Singh’ and ‘Kaur’ primarily as middle names.

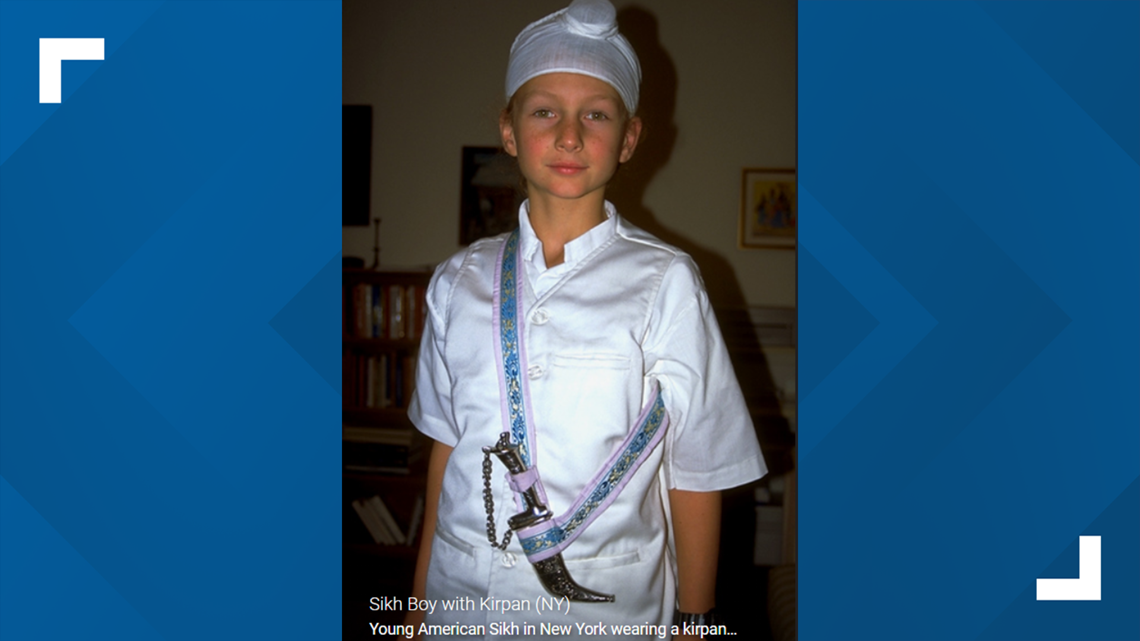

Sikhism’s last Guru also introduced five symbols that have become the markers of Sikh identity. They’re called the five K’s and only the most intensely dedicated Sikhs keep these distinctive emblems of Sikh identity. They include: uncut hair (Kes), a short sword or knife (Kirpan), a steel wristband (Karha), a wooden comb (Kangha) and shorts worn as an undergarment (Kacchera). According to Harvard University’s Pluralism Project, the Five K’s continually remind Sikhs of the ethical and spiritual implications of aligning one’s life with truth.

Singh or Kaur, Sikhs have been in America since the 1890s. So why do so few people know about Sikhs?

“In our religious tradition, we don't have a history of proselytizing. Because we're not going around announcing who we are and trying to convince other people to be like us. You know, there's no PR effort, at least not traditionally within the Sikh faith and so perhaps that has something to do with why folks don't know us as well,” said Simran Jeet Singh.

Unfortunately, when we do see Sikhs in the media, it's often in the aftermath of violence. Recent examples include the mass shooting at a FedEx facility in Indiana that claimed the lives of eight people. Among them- four Sikh FedEx workers.

FBI hate crime data shows Sikhs are the third most commonly targeted religious group in America -- behind Jews and Muslims.

“We experienced a significant uptick in hate [and] violence after 9/11 and that uptick has not slowed down,” said Simran Jeet Singh.

“After 9/11, right, people saw the face of the person who was responsible for it was wearing a turban,” said Vik Saluja. “Sikhs basically got mid-identified or mistargeted and they basically became collateral damage with the anti-Muslim or anti-Islam sentiment that came about.”

The targets of racism in America are constantly shifting based on national and international events.

“When my father first arrived in the 70s, he was perceived as the threat because he looked like, at least according to American sensibilities, he looked like the Ayatollah,” said Simran Jeet Singh. “When I was growing up in the 80s and 90s, the enemy shifted to Iraq, and I was called ‘Saddam’. And then 9/11 happens and the game again changed and the slurs that we received were ‘Bin Laden’, ‘Taliban’ and ‘Al Qaeda’. Racism is constantly shifting and adapting depending on who Americans perceived threat to be.

While Sikhs peacefully practice their religion, you also find them feeding the hungry and giving back to the communities they live in.

Through the tradition of Langar, the practice of preparing and serving a free meal to promote the Sikh tenet of selfless service, Sikhs serve an estimated 7 million meals a day worldwide.

The meals go to whoever needs them and have helped thousands facing food insecurity during the pandemic.

It’s a key component of the work Bhatia does with Sikhs of St. Louis, which has helped serve thousands of meals around the area.

“When we serve meals, we don't see caste, we don't see color, we don't see religion. It's for anyone and everyone. We all know actions speak louder than words. Sharing a food with someone connects you to them,” said Bhatia.

Recently, Sikhs in India have set up “oxygen Langars” for covid-19 patients struggling to find oxygen as virus cases continue to rise in the third-world country. Drive-through tents have also been set up outside Sikh places of worship- called Gurdwaras. No one is turned away.

Through these traditions, Sikhs continue to peacefully practice their religion around the world. At the heart of religion- a responsibility to help others.

“There's something really profound in this in this simple teaching that divinity is equally present in every single one of us,” said Simran Jeet Singh. “Because if you truly recognize the goodness in everyone and in the world around you then, even in the most difficult moments, it becomes possible to find silver linings and to find hope.”

Asian-American hate crimes

Across the country, there have been a number of disturbing acts of hate against Asian-Americans making headlines. How do these trends compare to years past and is there a connection to the pandemic?

The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino, studies these types of events. Researchers at the center looked at hate crime patterns in 2020 across 16 American cities.

In those 16 areas, overall hate crimes dropped by 7%. But anti-Asian hate crimes rose by 149% in 2020.

In 2019, there were 49 documented cases of hate crimes with anti-Asian bias in the 16 cities studied, while in 2020 there were 122 cases. That’s more than double the number of hate crimes from the year before.

Soo Nam, a senior corporal with the Dallas Police Department, says he’s been the target of racist behavior while on the job.

“As a police officer, going out, answering calls, there’ll be times, yeah, when I deal with either suspects of citizens, they’ll call me names. I’m from Korea, they call me ‘Go back to China,’ he said.

A report published in July 2020 from the Pew Research Center found a majority of Asian adults--58%-- said it was more common for people to “express racist or racially insensitive views about people who are Asian than it was before the coronavirus outbreak.”

Holly Nguyen, a restaurant owner in Dallas, has heard these types of comments from customers.

“A few customers came by and they made comments. They asked other team members, ‘Are you worried because you work with them?’ Implying Asian people have COVID,” she said.

Is the uptick in this type of behavior connected to the pandemic? The research suggests there is. According to the report, the number of hate crimes reported to law enforcement rose 40% from pre-pandemic levels in 2019 to 2020 when the pandemic was widespread.

And the Pew Research Center study found that “about 4 in 10 U.S. adults say it has become more common for people to express racist views toward Asians since the pandemic began.”

There are also organizations collecting data from across the country. Stop AAPI Hate has received thousands of self-reported incidents, the majority of which are not reported to law enforcement. Between March 19, 2020, and March 31, 2021, 6,603 incidents of Anti-Asian hate were recorded through Stop AAPI Hate.

Dr. Russell Jeung, a co-founder of Stop AAPI Hate, said there’s no mistaking the increase in hateful acts.

"There's been a surge of racism. There's been an increase in hate crimes and overall blatant racism and racist policies.”

Casual racism, microaggressions

When some people think of racism, they think of big acts of discrimination, but most of the time, racism happens more subtly.

Everyday racism often happens in the form of microaggressions.

Microaggressions are subtle interactions, whether they’re intentional or not…that create negative attitudes toward marginalized groups.

For example- an Asian-American is told their English is “perfect” but it’s their first language…or they’re asked “where are you from?” followed by “no…where are you really from” when their answer is one of the 50 states. Questions and statements like those imply that Asians can’t be “true Americans.” They’ll always be outsiders.

One of the ways we see casual racism clearly is through food. Many Asian-American children have heard that their food looks weird or their house smells funny…The TV show “Fresh Off the Boat” shows one example that so many of us have experienced.

“Ugh, what is that? It’s Chinese food. Get it out of here! Ying Ding is eating worms!”}

Maybe you’ve heard friends say they’ll have a headache after eating Chinese food because of the MSG…or you see menu items at a trendy new café that just appropriate Asian food terms without nodding back to their Asian roots.

It’s a tough conversation to have because no one wants to admit they’re being casually racist…but we need to start calling it out when we hear it. Every situation will be different, but try these things:

Ask for clarification: What did you mean by that?

Address the impact…When you say that, it’s hurtful and offensive because of these reasons.

We can only move forward if we call it as we see it…and encourage everyone to learn from what’s become so common.

Hypersexualization of Asian women

Oriental, Asiatic, superior beauty, quiet, expressionless. These are just some of the words that second-generation Japanese American filmmaker Kyoko Takenaka has received at bars from strangers. Takenaka, a performer, creator and artist, recorded real-life audio recordings over the span of seven years of racist come-on’s men have blurted out to them.

"I feel like most Asian American femmes can relate to that experience and you know if not one or all of those recordings I think has happened to Asian American femmes at one point or another in their lifetime,” said Takenaka.

Takenaka said recording these conversations was a way for them to make productive use of their anger and the microaggressions they experienced. Through a powerful ten-minute-long film called “Home,” Kyoko Takenaka touches upon complex issues, from Asian- Americans constantly feeling ‘othered’ to Hollywood’s historical-cultural objectification of Asian women.

The one scene that hits home hardest for many though, is the film’s ‘bar scene.’ The recorded one-directional exchanges have been viewed more than 300,000 times on Instagram alone.

Eye-opening and raw, the real-life documented conversations reveal firsthand how Asian women are often hypersexualized and fetishized.

“At the end of the day, all these experiences are non-consensual for Asian Americans. Recording was kind of a way for me to claim that space and moment for myself and know that even though I was in the process of dealing with that trauma, I knew that one day, it could be of use for someone else also explaining that similar experience and recording was the only way for me to do that," said Takenaka.

“Home” is now a source of inspiration for many Asian Americans, something Takenaka didn’t expect when they created the film three years ago.

Recent unrest and rise in Anti-Asian hate crimes led them to share this film publicly.

"If there was anything I could do with my art to unburden the labor of Asian Americans having to explain their own experience and to be validated during that time, then I wanted it to be of use and I know that that film could have been of use at that moment,” said Takenaka.

They plan to continue rallying for the Asian American community through their art. While Takenaka identifies as non-binary, they hope for Asian American femmes to be liberated from these lines society has drawn for them.

“I just feel like I think the goal of Asian American women for me is to not be boxed, and not be stereotyped into one definition of what that looks like, feels like, what that is, what that could be like. I really would just love for Asian American woman to mean ‘human being,’” said Takenaka.

Moving forward

It started in metro Atlanta.

A white gunman was charged with killing eight people in three separate spas. Six of the victims were Asian women. Prosecutors are now seeking the death penalty against Robert Aaron Long, the suspect in the deadly shootings in March.

The string of gun violence occurred in metro Atlanta, but it sparked a movement across the United States. Across the nation, communities came together to hold memorials, rallies and vigils to remember the lives lost and to fight against a spike in Asian hate crimes.

“It was really disorientating when it all happened, but we knew we needed to start working right away,” said Arah Kang, a board member of the nonprofit organization Korean American Coalition-Metro Atlanta.

Physical and verbal attacks against Asian Americans have grown significantly in the past year due to the false belief that Asian people are to blame for the spread of the coronavirus. Anti-Asian hate incident reports nearly doubled in March, according to the organization Stop AAPI Hate. Former President Donald Trump even referred to COVID-19 as the “China virus” or the “Kung flu.”

Those harmful words have incited fear among Asian American communities, but amid all the devastation and trauma, Asian Americans have used the pandemic-fueled hate to spread more awareness around hate crimes. Asian American and Pacific Islander organizations have also been hard at work to support communities impacted by the violence.

Kang said almost immediately after the news of the Atlanta-area shootings, she was involved in organizing a local vigil. She said what she didn’t expect was the overwhelming response to it.

"We went from a local vigil, and then it became a nationwide vigil, and within a matter of days, it turned into a global vigil,” she said.

Kang said the experience made her realize how much more work there was left to be done.

“We wanted to be more proactive. We wanted to make a statement about combating Asian hate crimes,” Kang said. “For me, it was hard for me to wrap my head around the question, ‘Why did it take a mass shooting for the Asian American community to be taken seriously?’”

There’s also been growing movement on the national level. Last month, the Senate overwhelmingly passed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act, which would establish a process for hate crimes against Asian Americans to be investigated and documented by state and federal law enforcement officials.

“Passing this bill makes it very clear that hate and discrimination against any group has no place in America,” said Senate Majority Leader and New York Democrat Chuck Schumer. “Bigotry against one is bigotry against all.”

Still, Asian Americans say they want to see more change. That includes advocating for more education around the experiences of all minority groups.

“We really have to be open about learning and unlearning because white supremacy has seeded into our community and other Black, Indigenous, People of Color communities. The learning has to be continuous. There’s no pinnacle,” Kang said.

Change doesn’t always have to be big. It can start small – with daily actions. According to Stop AAPI Hate, that includes making donations to groups actively fighting anti-AAPI discrimination. People can also support local Asian or businesses.

Most of all, change starts with recognizing the good that’s happening in AAPI communities.

“We don’t want to be just defined by our trauma,” Kang said. “We also want to celebrate Asian joy.”

TEGNA's Katie Kim, Tiffany Liou, Shern-Min Chow, Thuy Lan Nguyen, PJ Randhawa, Matthew Torres and Megan Yoder contributed to this report