FAYETTEVILLE, N.C. — In 2021, 798 people in the U.S, died on the job as a result of exposure to harmful substances or environments, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the most in a ten-year span.

Bradley Zipp, a 51-year-old mechanic, was one of those people. He couldn't even make it a full month on the job at Valley Proteins before his September 2021 death. Fatal levels of hydrogen sulfide at the Fayetteville, North Carolina, animal byproduct processing plant killed Zipp and a coworker.

His sister, Laurie Toth, who lives in Pennsylvania, would get calls from her brother early in the morning. Those calls are one of the things she misses most about her younger brother.

"I'll never hear his voice again, and they took that from me," Toth said.

In all, 179 people in North Carolina died from a fatal injury at work, according to the federal government. When an employee is injured or killed on the job, the North Carolina Department of Labor and South Carolina Occupational Safety and Health Administration often impose fines on employers. Those penalties are designed to help deter future hazards that lead to injury or death.

However, a WCNC Charlotte investigation found employers rarely face hefty fines. In fact, an analysis of federal data revealed the median fine is just $5,000 in the Carolinas, in part, because companies regularly negotiate reduced penalties.

"That is a disgrace," Toth said of WCNC Charlotte's findings. "I think they should be ashamed of themselves."

Public records show a Valley Proteins employee found Toth's brother face down, alongside a coworker more than an hour after the men unjammed an auger. After an investigation, the state cited the company for several violations and issued fines totaling $13,750, according to federal data. Valley Proteins is contesting every one of its citations, public records show.

"I feel like my brother and the co-worker were sent down to the gas chamber," Toth said. "This is a company that makes millions and millions of dollars and they're trying to appeal measly pennies for two human lives?"

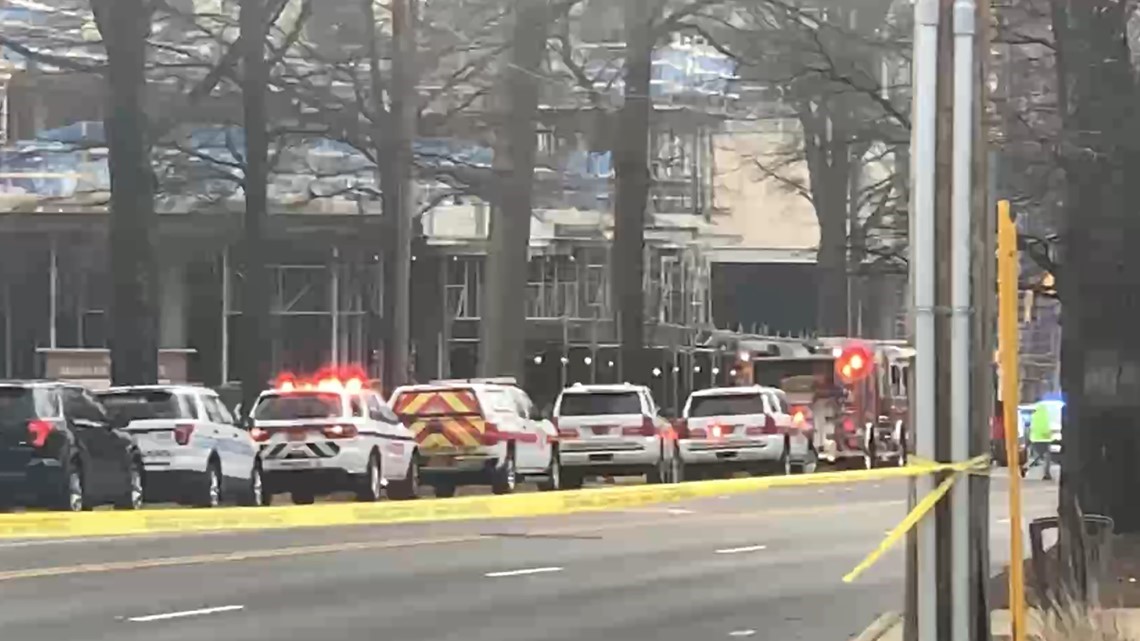

This approach is far from unusual. WCNC Charlotte started investigating workplace death penalties earlier this year after three construction workers died uptown when scaffolding collapsed. Their workplace death investigations remain under investigation.

The WCNC Charlotte team analyzed non-COVID Occupational Safety and Health Administration fatality reports in the Carolinas since 2020 and found, when state and federal regulators penalize companies for workplace deaths, roughly 43% of the time, the employers fight those fines and/or settle for lower penalties.

WCNC Charlotte has created a searchable database of workplace deaths dating back to January 2020. You can search by type of death, state, city, or date to see incidents in both North Carolina and South Carolina. You can also copy and paste the OSHA inspection number into OSHA's website to find more details.

"How does that incentivize a company to do more to protect its employees?" WCNC Charlotte asked North Carolina Department of Labor Chief of Staff Scott Mabry.

"We will go to extreme lengths to try to defend those, but oftentimes the trade-off is to try to get it corrected as soon as we can so that the hazard does not reoccur," Mabry responded. "We try to stick with what we can because we know it means something to those families."

Mabry said if a company contests the original fine, which is calculated based on severity, they're not required to correct any hazards until their appeal is resolved. That process can take months or even years.

He said that's why the state regularly settles early on for reduced penalties in exchange for immediate corrective action, often asking for extra safety measures above and beyond OSHA standards. Other times, a hearing examiner or judge, upon review, directs the department to lower the fine.

"Our goal is to get the hazard corrected. What we don't want is for this to reoccur," Mabry said. "We're certainly aware of the pain and issue that (families) have and we continue to do our best to try to maintain the penalties as we can, but oftentimes it's necessary to take that step to get that case adjudicated and wrapped up without it dragging on for years, which we really don't want to do."

North Carolina increased its maximum fines just last year, which doubled the previous amounts in hopes higher penalties will deter unsafe working conditions. Mabry said the new maximum penalty for a "willful" violation (the most severe) is roughly $145,000 and more than $14,000 for a "serious" violation (the next step down).

Mabry pointed out, when you look just at the fines themselves, North Carolina retains roughly 90% of all penalty dollars, which he said is better than most.

"We've done a good job, I think, compared to our states around us and the federal rates as well to be able to maintain as much as we can," he said.

Fun-loving, competitive and high-spirited, Toth's younger brother didn't get to know her until both were well into adulthood.

"We were in foster homes at a young age, so we were all separated," Toth said. "We didn't have that long of a period in our lives to reconnect and I feel like Valley Proteins robbed us of that."

Even so, he made his time count. Zipp would regularly send Toth's autistic son gifts when he did well in school.

Now, the family has separated yet again. More than a year and a half later, his phone call isn't the only one she's waiting on.

"There's no communication at all," she said of the workplace investigation process. "They don't even call me. I know nothing."

Toth is desperate to find out how the state will ultimately punish Zipp's employer for failing to protect him. She believes the penalties should be much more severe.

"I'm very. very frustrated. I lose a lot of sleep over this. I get anxiety. I have nightmares thinking about how my brother died, what his last thought was," she said. "Hit them where it hurts and that's their pocket. If there were a fine of a million dollars, do you think this would happen again? I don't think so."

Valley Proteins' parent company declined to comment for this story, but a document obtained by WCNC Charlotte shows the company has since made several changes. The company's list of corrective actions includes the addition of a new ventilation system and new monitoring for hydrogen sulfide at all times.

The document goes on to say Valley Proteins still questions whether hydrogen sulfide was the actual cause of death in this case.

An autopsy report determined the cause of death was "probable of an accidental death due to asphyxia due to hydrogen sulfide gas exposure."

Contact Nate Morabito at nmorabito@wcnc.com and follow him on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.