CHARLOTTE, N.C. — In Baltimore, families living in low-income and crime-ridden neighborhoods got extra money to move to the suburbs.

In New York City, tenants threatened with eviction received free help from lawyers.

And in Chatham County, Spanish-speaking immigrants who were being kicked out of a mobile home park got help from a non-profit.

Like most major American cities, Charlotte is suffering from a severe shortage of affordable housing.

More than a third of households in Charlotte are “cost-burdened,” which means they spend more than 30% of their income on housing, according to a city report. The federal government says that leaves them with too little money for food, clothes, medicine and other basic needs.

Charlotte would need roughly 34,000 more units of affordable housing to meet the need, mostly for families and others who make less than $25,000 a year, the report says.

But Charlotte — North Carolina’s biggest city — has failed to take significant steps that have helped other cities and counties address the problem and reduce displacement, homelessness and economic inequality, housing activists say.

Fast-rising rents and home prices, population growth and stagnant wages have been major factors in Charlotte, but specific decisions by developers and city leaders have had negative consequences that reverberate today. Some are as old as the former Brooklyn community, the African-American neighborhood razed under the banner of urban renewal. Others are as modern as the creation of Ballantyne and Charlotte’s light rail line.

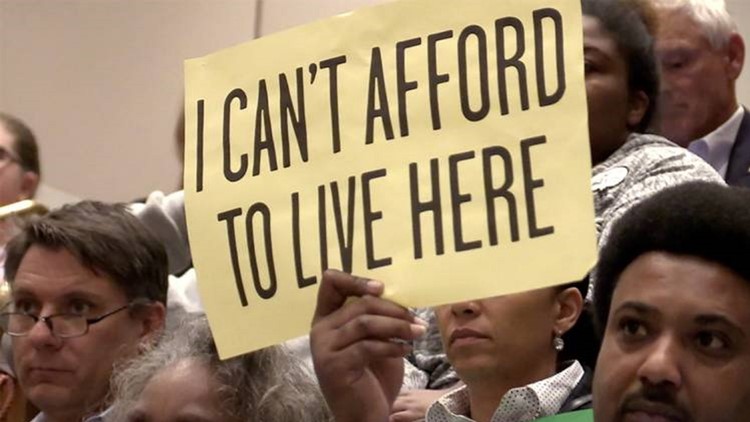

Over the next few months and possibly beyond, the Charlotte Journalism Collaborative will be exploring the city’s affordable housing crisis through a solutions journalism lens in a project called “I Can’t Afford to Live Here.” Reporters will search for responses to the problems by looking to other areas of the country.

The collaborative is in partnership with the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit whose mission is to spread solutions journalism practices to newsrooms on this continent and beyond. The Charlotte Journalism Collaborative is funded by the Knight Foundation. Its members are The Charlotte Observer, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, La Noticia, Qcitymetro , QNotes, Queens University of Charlotte, WCNC, Free Press and WFAE.

As part of the effort, former Observer reporter Pam Kelley and other reporters will examine some of the key moments that set the pattern for Charlotte’s current housing environment.

“The status quo is not working,” Fulton Meachem, chief executive officer of the Charlotte Housing Authority, said of his agency’s clients’ ability to find low-cost housing in neighborhoods with solid schools, good jobs and transportation. “We’re 50th out of 50 (big cities in economic mobility) for a reason.”

In response to a lack of affordable housing, Charlotte and Mecklenburg County leaders and big businesses have pledged to spend tens of millions of dollars to build new affordable housing, renovate existing homes and provide rental subsidies. Much of the money will come from $50 million in bonds voters approved in November.

Housing activists and social justice groups said Charlotte should emulate programs that have worked in other places.

Here’s how some other cities and organizations have tried to tackle the affordable housing shortage:

MOVING UP?

Baltimore is one of the nation’s most troubled big cities.

It has one of the highest murder rates in the country. More than one in five residents live in poverty.

In 2005, a federal judge ruled that the government was responsible for segregated public housing in Baltimore, a violation of federal civil rights law.

That’s how the Baltimore Housing Mobility Program grew. The program takes public housing residents — typically African-American women and their children living in impoverished neighborhoods — and offers them a higher housing allowance than the federal government normally provides if they are willing to take classes and move into new neighborhoods. The new neighborhoods, called “Opportunity Zones,” have stronger schools, more job opportunities and public transit, according a 2018 report from Vox, a news website.

Since 2005, more than 4,000 families have participated.

Successes in Baltimore and other cities such as Chicago and Dallas prompted federal lawmakers last year to set aside $28 million for demonstration programs for an idea that started in the 1970s.

The Charlotte Housing Authority started its program about a year ago and studied the model practiced in Baltimore. But only seven families have participated so far.

The issue is significant because research suggests that where children are raised significantly impacts their ability to climb out of poverty. A prominent national study found Charlotte ranked 50th — dead last — among the nation’s biggest cities for economic mobility.

More than 4,000 families in Charlotte rely on subsidies from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to help pay rent. Under the program, families and others with low incomes pay 30 percent of their income toward rent and the government covers the rest.

But landlords’ refusal to accept tenants who use Section 8 vouchers undercuts the government’s goal of helping families escape poverty and move to the neighborhoods with good schools, jobs and transportation, said Meachem, leader of the Charlotte Housing Authority.

The agency plans to help as many as 100 families move to neighborhoods with better opportunities by providing them with bigger housing allowances, which would give them the ability to pay for housing in areas where rents are higher.

“It is not housing choice if you can only choose one poor neighborhood or another,” said Barbara Samuels, managing attorney for ACLU of Maryland’s Fair Housing Project, which was part of the lawsuit that brought about Baltimore’s program. “Living in a distressed neighborhood is not good for kids. We have a lot of evidence that children are being harmed.”

FORCED OUT

New York City, San Francisco and Newark, N.J., have recently enacted laws ensuring some people facing eviction get legal representation in court, according to an April report from National Public Radio.

So-called “right to counsel” programs attempt to address one of the most enduring disparities in the American justice system: Most landlords have legal representation in eviction court while most tenants do not.

A recent study in New York found evictions decreased more than five times faster in areas where the new rules were in effect than in those that were not included.

Charlotte’s eviction rate is nearly twice as high as some of its peer cities such as Atlanta, Nashville, Kansas City and Tampa, according to research.

But Legal Aid of North Carolina represents about 250 of the 29,000 people who face eviction in Mecklenburg County every year, according to a Charlotte Observer report from March.

A proposed budget from Mecklenburg County Manager Dena Diorio includes $500,000 to expand Legal Aid’s office and provide assistance to tenants.

WALL STREET MOVES INTO TRAILER PARKS

Over the last three years, Wall Street private firms have bought thousands of mobile home parks and raised the price to live there.

Wall Street titans such as the Carlyle Group and the Blackstone Group have taken ownership of more than 100,000 home lots, says a recent report from watchdog groups.

The firms have reaped handsome profits, according to a report from The Washington Post.

Often Spanish-speaking immigrants have paid the price.

Large numbers of Latino families in the Charlotte area live in mobile home parks, where prices have shot up.

Residents often own their trailers, but must pay lot rent to the park owner. As corporate landlords have raised the rent, activists say residents have little choice but to pay up because they can’t move.

In many cases, the trailers are prohibitively expensive to move or contracts forbid owners from moving them.

Activists say that means that immigrants have been victimized by predatory operators, including some who charge them more and refuse to make needed repairs.

They said Charlotte leaders have failed to give the issue enough attention and help immigrants advocate for themselves.

Activists point to a recent case in Chatham County.

In November 2017, Mountaire Farms announced plans to expand its poultry processing operations and bought Johnson’s Mobile Home Park in Siler City.

The company offered tenants money for their homes and ordered them to leave in a few weeks.

But the nonprofit organization El Vínculo Hispano-Hispanic Liaison organized tenant protests and made appeals to the Chatham County Board of Commissioners. By March 2018, the group renegotiated with Mountaire Farms and residents got a better price for their homes and more time to leave.

Charlotte city leaders have acknowledged they have not studied the impact of corporate landlords on rents, despite Wall Street firms buying thousands of houses in recent years.

SAFE PLACE TO STAY

The number of Americans age 50 and older who identify as LGBTQ is likely to double in the coming decades to more than 5 million, according to a study from the University of Washington.

Another report found nearly half of LGBTQ older adults have faced rental housing discrimination, according to SAGE, a national advocacy group for older LGBTQ people.

The organization is conducting a campaign to bring more attention to discrimination senior same-sex couples face in trying to find housing in retirement communities and nursing homes.

In other urban areas around the country, there are apartment buildings like the John C Anderson apartments in Philadelphia that offer its residents a LGBTQ-friendly senior community.

But in North Carolina, there are few residential communities and apartment buildings that perform direct outreach.

One is Care Free Cove, a sprawling residential neighborhood near Boone that developed by a lesbian couple from Florida. Residents buy a plot of land and build their own homes.

Fred Clasen-Kelly of The Charlotte Observer, David A. Moore and Jim Yarbrough of QNotes, Diego Barahona and Hilda Gurdian of La Noticia, Glenn Burkins of Qcitymetro, Jennifer Lang of WFAE and Amy Lehtonen of WCNC contributed.