CHARLOTTE, N.C. — On Sept. 11, 2001, when terror came to our shores, the school day was just beginning for millions of students. It was before the age of smartphones.

Many students began hearing what happened through the rumor mill, or on the TV that was mounted on the wall in their classrooms. Teachers had to make a choice: do you tell the students what just happened, or do you shield them?

Here are some of the accounts of educators who were teaching in classrooms in North Carolina that day.

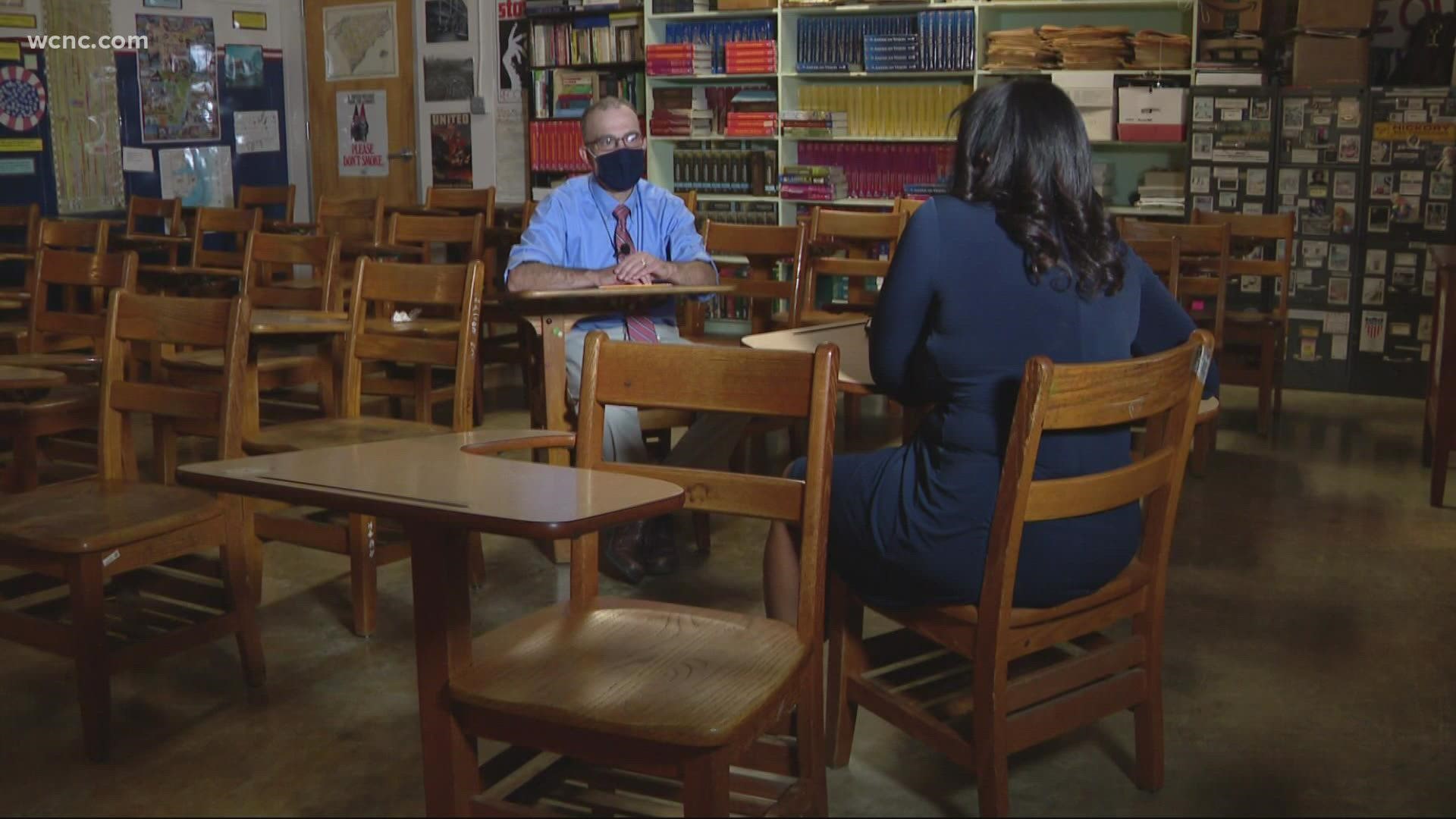

Drew Daniels: Social Studies Teacher, Hickory High School

“I was sitting in that chair right there,” said Drew Daniels, a social studies teacher at Hickory High School, gesturing to a chair in the corner of his classroom.

Daniels was between first and second periods when another teacher walked into his classroom.

“I remember he didn’t even look at me, he never broke stride, he said, ‘Go to CNN,'" Daniels said.

He did not have a television in his classroom. Instead, he pulled up the news outlet’s website and saw images of a burning building.

“All I could get was an article and maybe some photos,” Daniels recalled. “It was about the time that they were confirming that a second plane had it.”

Daniels knew in a matter of moments there would be two dozen students walking through his classroom door.

“I told them,” he said. “I don’t know if that was the right decision or not.”

Daniels said his students had lots of questions he was unable to answer. He was still processing the events as they were unfolding, but the history teacher knew he was witnessing history.

“I wanted to project the magnitude as I understood it,” Daniels said. “But I was also conscious of the fact that I needed to remain collected.”

Some of his students worried whether the Charlotte area could be targeted next.

“There was some fear,” he said. “I remember students asking, ‘Do you think we’re safe?’”

Daniels admitted he did not know how to react.

It wasn’t until he got home that he was hit with the weight of the day.

“That day, coming home, my daughter was 18 months then; I remember her looking up smiling, recognizing me,” he said. “I was aware then how much the world was different from the last time I had laid eyes on her.”

RELATED: 20 years after 9/11 terrorist attacks, legacy of ‘the man in the red bandana’ stronger than ever

Back in his classroom, 20 years later, the walls, desks, cabinets and doors are covered with posters and memorabilia from some of the most important moments and people in U.S. History -- 9/11 is not on the wall.

The newest chapter in his students’ U.S. History book is the darkest chapter in modern U.S. History for their teacher -- and one he is not willing to relegate to the past.

“For my students now it really is history,” Daniels said, “For me, it’s still personal.”

Daniel Bryant, AP History teacher, A.L. Brown High School | Kannapolis, NC

Daniel Bryant has been a student, teacher and lover of history for most of his life.

“I think everybody can find themselves in the stories,” Bryant said, seating in one of his students’ desks at A.L. Brown High School in Kannapolis. “I think every generation has that moment that sticks in their brain.”

That moment for a generation happened while Bryant was teaching the first period of his A.P. History class on Sept. 11.

Bryant said still remembers it like it was yesterday: “A teacher came running up the hallway and said, ‘Turn on the TV, we’ve been attacked!’”

He immediately turned on the television for his class of high school students and saw one of the twin towers heavily damaged.

“We watched on television as the second tower had been hit,” he said. “The classroom was very somber and it was kind of a weight in the classroom and you kind of really don’t know what to say.”

Bryant’s lesson plan went out the window. He and his students sat transfixed watching the news coverage.

He doesn’t remember how long they watched; it was long enough that the principal came over the loudspeaker and told all of the teachers to resume regular instruction.

“That was impossible,” Bryant said. “Every second I got, the TV was back on and I was riveted.”

He knew the teenagers had questions. As advanced students of history, many of them had questions that challenged his own understanding of the events. But as the days went on, Bryant said the questions slowed down and eventually stopped.

“A lot of times we didn’t talk about it because I think they wanted some normalcy back in their lives,” Bryant said.

At a time when so much was unknown, Bryant made it his mission to make his class as safe a place as possible. It's something he is doing again now with his students who are facing what he believes will define their generation: COVID-19.

“COVID may be their moment,” Bryant said. “It remains to be seen.”

Robert Brown, Former social studies teacher at Crest High School

Over the course of his decades-long career, Robert Brown has taught or coached thousands of students. But there’s nothing like the ones who sat in class with him on Sept. 11.

“When you do go through a world-changing event, the people that you are around, they help you get through it and understand it,” Brown said, pausing for a moment, determined not to shed a tear. “It is a touchstone that we all have in common. We saw this together we experienced this together and we had to figure it out together.”

Brown had a classroom full of 16-year-old advanced social studies students that fateful morning. Another teacher called out the words that Brown can still hear replaying in his mind.

“He said, ‘Robbie. A plane has hit the World Trade Center,” Brown recalled. “At that point, you’re like, ‘What has happened?’”

Brown saw the building smoking on his television screen and saw his students with puzzled faces looking back at him.

Brown said he knew in his mind “that wasn’t an accident.” But he also knew he wanted to be the one to tell his students.

“If I had tried to turn that off, they would have found their own way to find out, so it was either I’m going to have to walk them through it or they’re going to find out on their own and I’m not having that,” Brown said.

Moments later, another crash.

“It wasn’t 10 minutes later when the second one hit,” Brown said. “It was almost a collective [gasp].”

Brown said they all spilled out into the hallway yelling in disbelief, questioning if everyone else had just witnessed what they did.

"That’s when you knew, really, really quick that the world had changed,” Brown said.

So, they spent the next period together glued to the screen, asking and answering questions.

Brown said, as a person who studied current and world events, there was one name that kept popping into his brain.

“I told them to remember the name Osama bin Laden," he said.

Little did he know, at the time, that it would be a name none of them would forget.

Years later, he still keeps in touch with many of the students in the class.

“It’s an incredible bond with them,” Brown said.

For Brown, that bond will be unbreakable, because it was formed the day the world changed.

“I look at things much differently. That’s a sea change or a paradigm shift in my mind,” he said. “It’s not an ‘if’, it’s a ‘when' -- and the ‘when’ happened that day.”

Beverly Snowden, Former 7th-grade social studies teacher

Beverly Snowden stood frozen outside of her 7th-grade classroom for a moment.

Some fellow teachers had just beckoned her outside to whisper the news of a plane that had hit one of the twin towers. She couldn’t figure out how to move or what to say.

“I had to remain composed,” Snowden said.

But once she walked through those doors, she would not only have to face her students, but also her son, who was among the children in her class that year.

Her eyes well up from the thought of it.

“I loved all of the children,” she said.

They made the decision to go downstairs as a group to watch what Beverly had told her students was “a national concern.”

But before long, that concern would become personal.

Snowden’s brother worked at the Pentagon. His phone was dead.

“I knew that my younger brother could be among those who died and there was no way to reach him,” Snowden said.

She and her baby brother had always been close, but he and her son shared a bond unlike any other. She couldn’t give him the solace he desperately needed.

“My son, in particular, kept coming up to me as his mother and his teacher coming up to me wanting to know about his uncle who he loved and he loves so much,” she recalled.

Snowden tried reaching her brother throughout the day but could not get through. She stumbled through the day trying to help her students with their own grief and fear, while silently coping with her own.

Hours later, Snowden received word that her brother had survived. Many of the men and women in his section of the building had been killed.

“Thank God he lived through that day,” Snowden said.

In the days that followed, Snowden worked to process her own feelings and realized her students may have the same desire.

She scrounged up two large refrigerator-sized boxes, draped them in red, white and blue, and stuck them in the center of her classroom. And then she told her students to write whatever came to mind.

“To write about their emotions and what they saw and what they experienced and how they felt about themselves,” Snowden said. “They were putting all of that in writing and it was absolutely beautiful.”

When the students finished, she laminated each one of their writings and posted them on the twin tower memorial she’d erected in her classroom.

That tribute had a home in her classroom for much of the year.

“In some strange way, it allowed those people whom we lost to be alive in our classroom, we were honoring them and we were remembering them.”

Snowden’s son, now 33 years old, was forever changed by that day. He grew up to be a Marine.

“He wanted to be one of those that stands up for our country," she said. "And 9/11 had something to do with that.”

Contact Tanya Mendis at tmendis@wcnc.com and follow her on Facebook and Twitter.