The secret story behind 85 Black students who were the first to integrate a public school

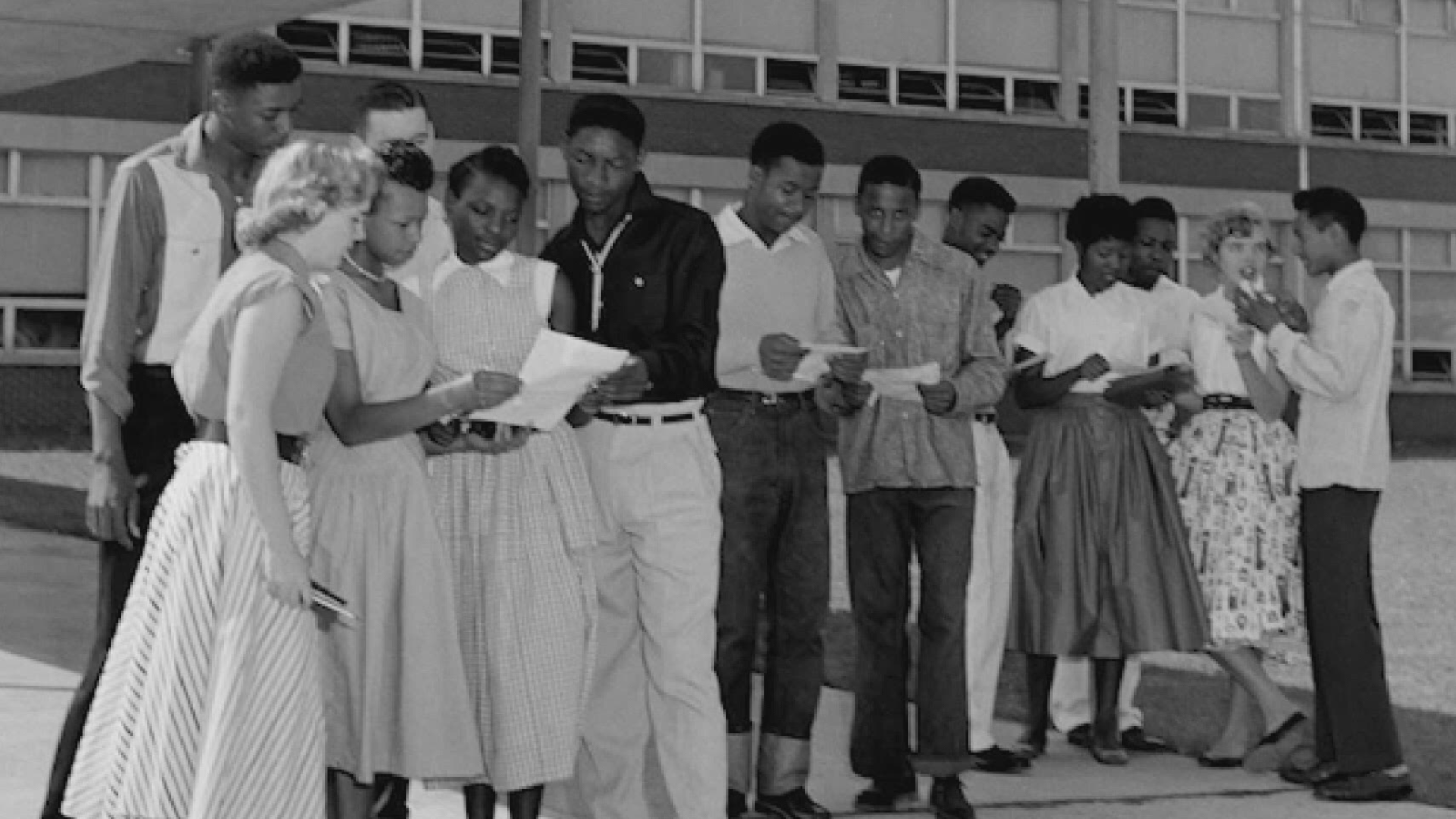

In September 1955, the Oak Ridge 85 from the historic Scarboro community became the first to integrate a public school in the southeast.

One year before the Clinton 12, two years before the Little Rock Nine and five years before Ruby Bridges, there was the Oak Ridge 85.

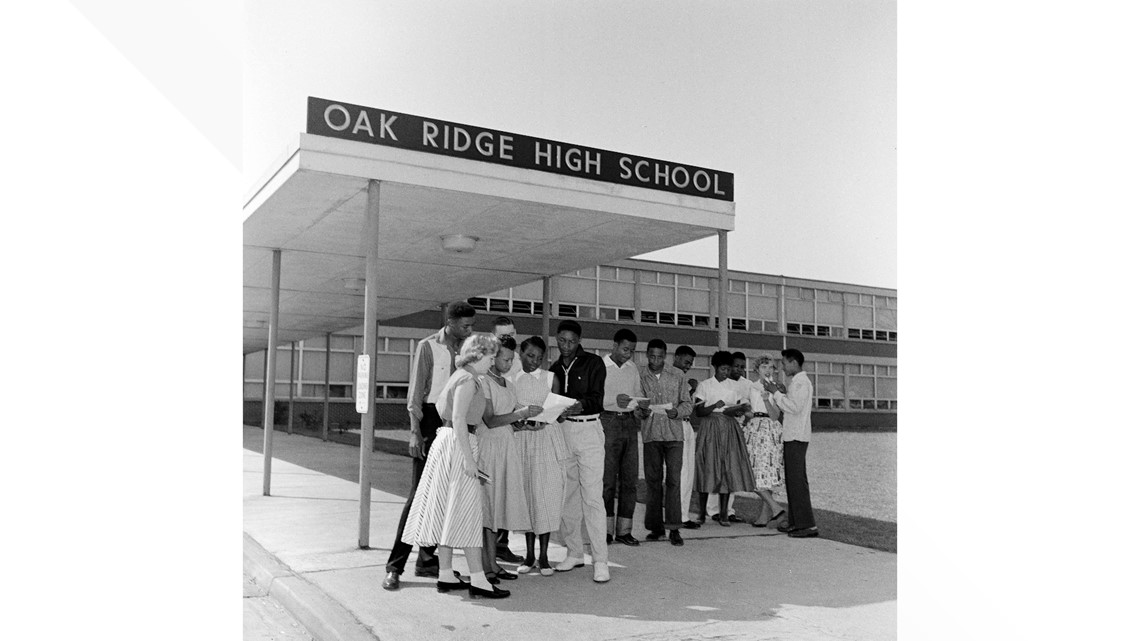

On Sept. 6, 1955, 85 Black students from the historic Scarboro community integrated Oak Ridge High School and Robertsville Junior High.

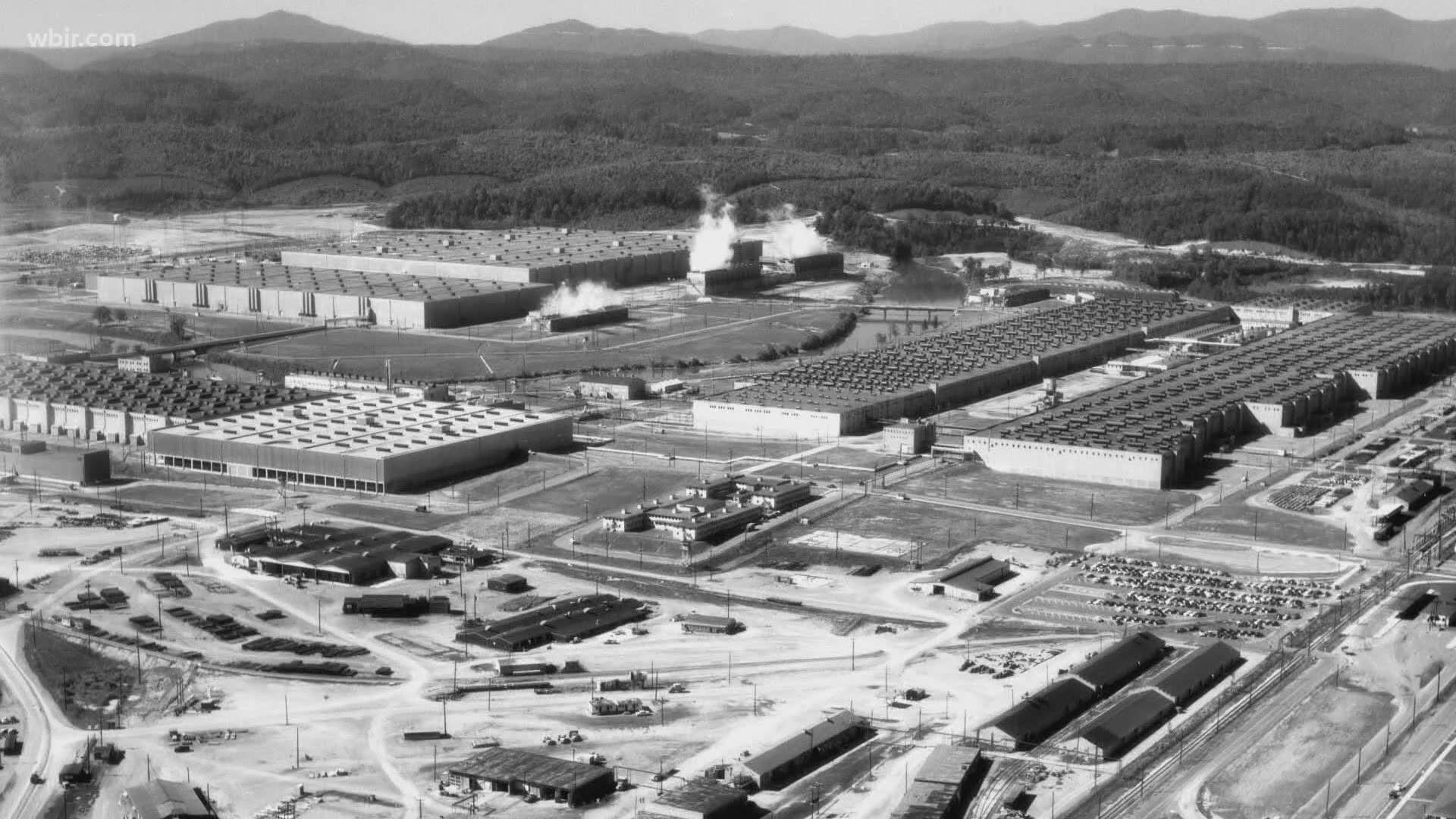

It was a controversial idea, envisioned at least a year before the Supreme Court settled Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954, and it originated right here in East Tennessee's Secret City.

The Scarboro Community

To start our journey into the story behind these 85 students, we need to know about their origins in the years leading up to their history-making integration in 1955.

Inside the "Secret City" is a predominately Black community named Scarboro.

"Scarboro history is Oak Ridge history and vice versa," said John Spratling, a coach and history teacher at Oak Ridge High School.

Despite segregation and Jim Crow laws, Black children from this community helped change the course of history in Tennessee and the southeast by becoming the first to integrate in the region.

"I always thought Scarboro was another little city within Oak Ridge," said Rose Weaver, a community historian. "In the 1940s, those conditions were not good."

In the 1940s, Scarboro was a woodland area where Black residents were separated from the rest of the community, living in hutments. These hutments were 14x14 frame units with no plumbing and a coal stove for heat.

Spratling said husbands and wives were not allowed to live together, separated by a wooden fence. Black children were not allowed to come into the greater Oak Ridge community.

"It was a different time. It was a different place," Oak Ridge Mayor Warren Gooch said.

From the 1940s to the 1950s, the Scarboro community moved from the woodland area to its current location in Gamble Valley, roughly two miles outside of Oak Ridge.

"It became more of a hustling and bustling community," Weaver said.

Mayor Gooch said Scarboro community members were employed at the government facilities, the plants and in the school system in Oak Ridge in the 1950s.

"In that time frame, most of the people that lived in the Scarboro community was janitors. They did not have any professional jobs, although some had college degrees, but they could not have a working or scientific layoff or what have you," said LC Gipson, one of the Oak Ridge 85.

Originally, there was not a school for Black children. They were usually bussed to Austin High School in Knoxville. However, as more and more of their parents were recruited to the area, the need for a school in the community grew.

"The federal government says, ‘Well, we got to build a school for these Negroes. They’re here,’" Weaver said.

Scarboro School became the only school in the community for Black elementary, middle and high schoolers.

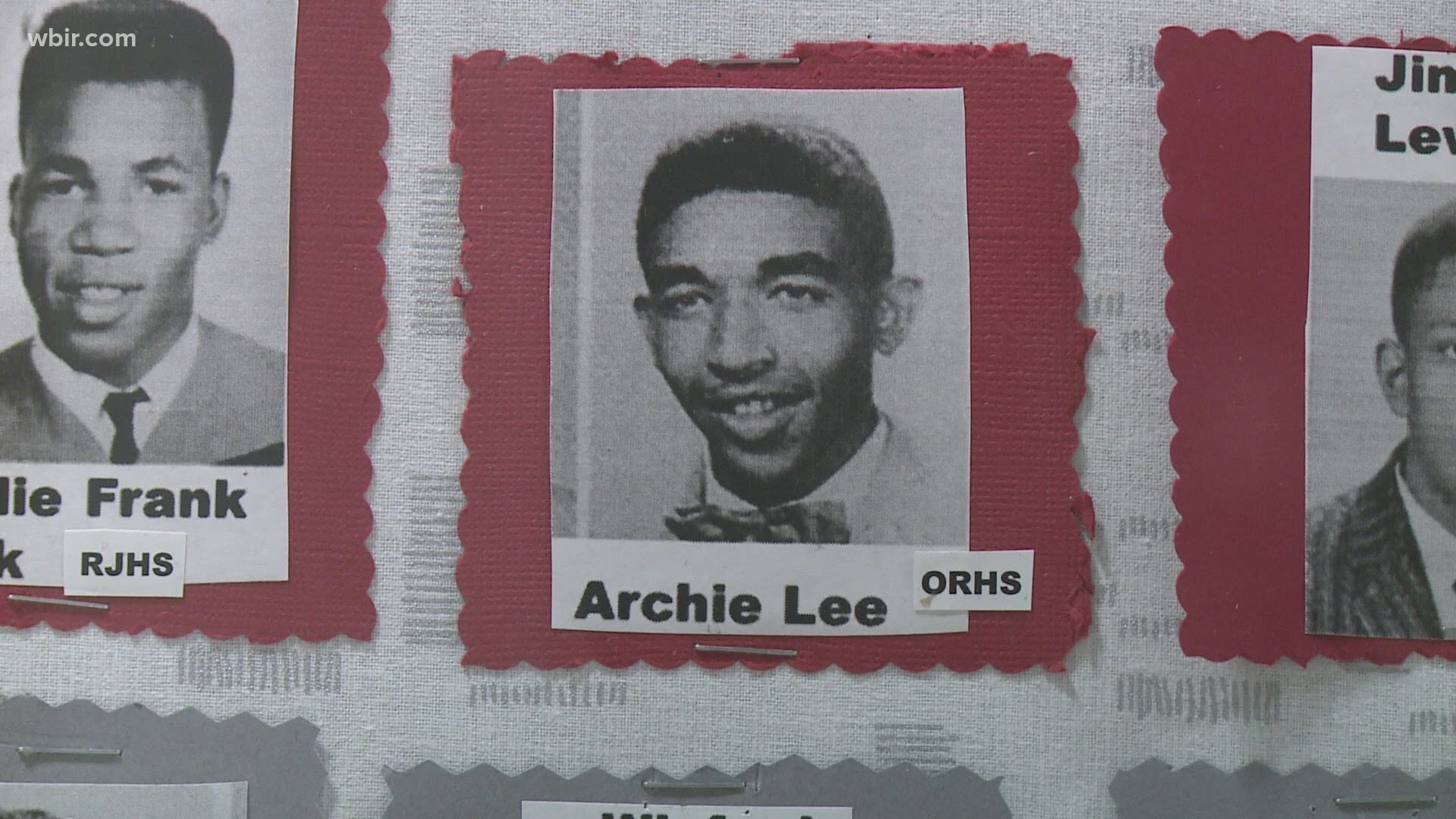

Archie Lee, who would become one of the 85, was at Scarboro from 9th to 10th grade and served as president of the 10th grade class.

“The teachers were outstanding, but we didn’t have the tools and the resources to advance,” Gipson said.

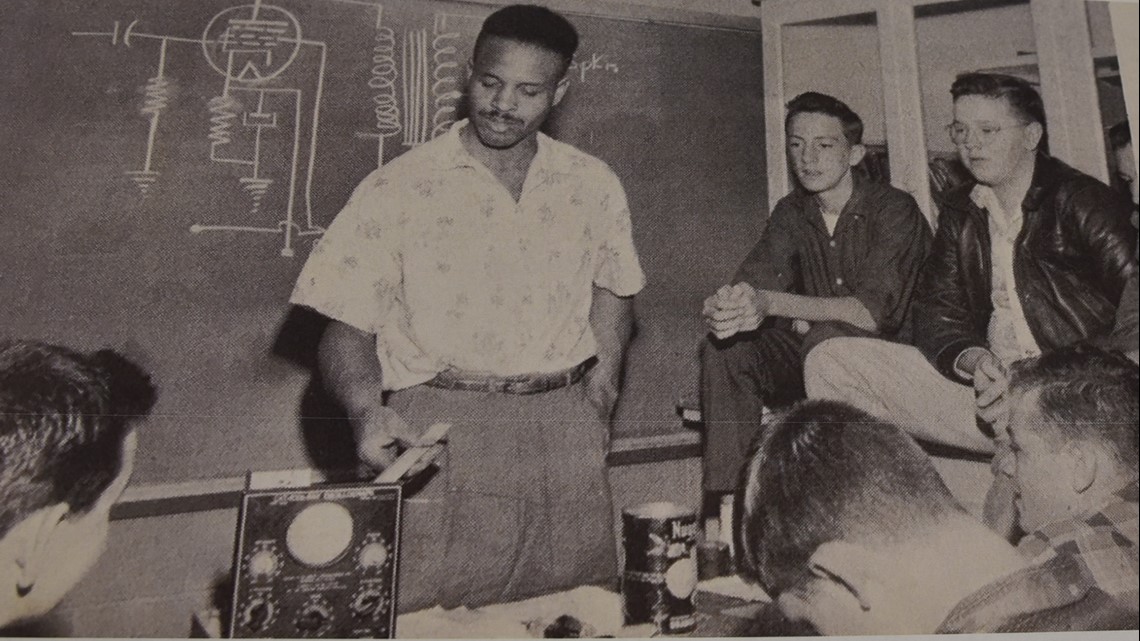

One of those teachers was Fred Brown, the namesake of Fred Brown Hall at the University of Tennessee. He started out as a teacher at Scarboro School, moved with the 85 to Oak Ridge High School and then eventually to UT.

To this day, education is at the heart of this community with streets named in honor of historic Black colleges and universities across the U.S.

For this reason, it seems fitting that one big decision in the 1950s changed the course of learning for generations to come and turned 85 students from this community into leaders.

The Decision

Oak Ridge, also known as the Secret City, was not actually an official city in the 1950s.

It was operated under federal control through the Atomic Energy Commission because of its involvement in the Manhattan Project. It was led by an advisory council that had no political influence.

Dr. Waldo Cohn was the chairman of the Town Advisory Council and one of seven elected members when the idea of integration came up in the community.

"The Department of Energy had been talking about it, but Waldo Cohn really was pushing," Gooch said.

In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower issued an executive order that all Army bases that had schools would desegregate those schools.

“I said, ‘Perhaps we could petition Eisenhower to include the Atomic Energy Commission facilities,’” Cohn said in an archived interview. “So, I constructed a very simple petition to the President.”

Cohn circulated the petition to all the members of the Town Advisory Council for discussion and a vote. Five members voted "aye" and the remaining two said "no."

The vote passed. The petition was sent to President Eisenhower after the group's last meeting of the year in December 1953.

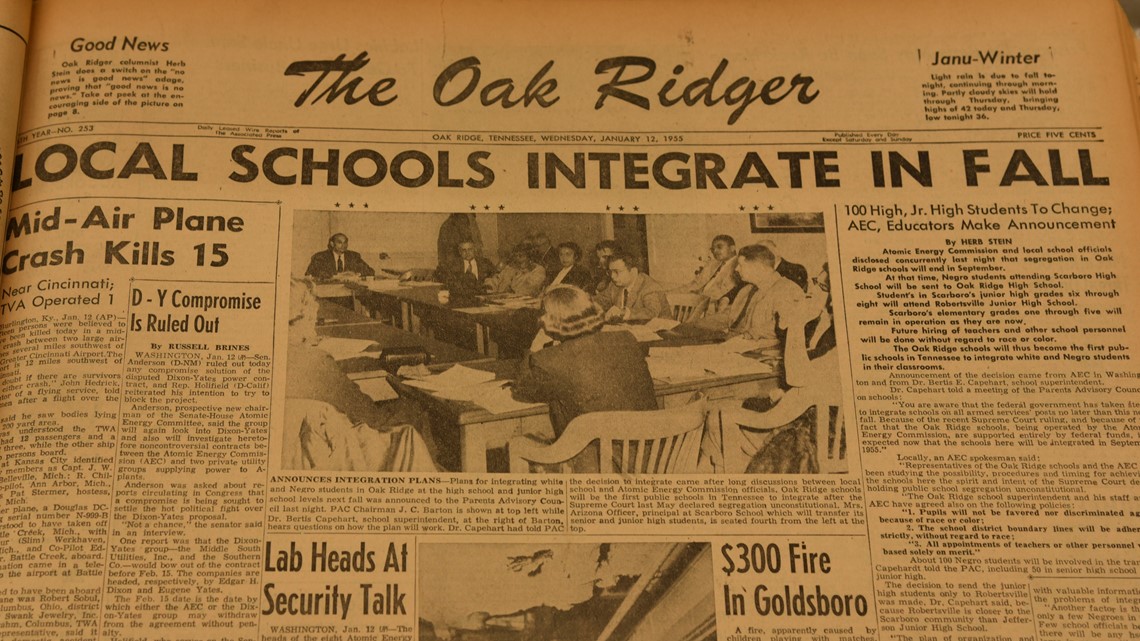

“The next day, this hit the front page of the Oak Ridger. The day after that, the egg really hit the fan," Cohn said in his interview.

Weaver said Cohn received a lot of backlash, and people wanted to take him off the advisory council.

"I mean, we were in the middle of, you know, Appalachia, we’re in the south. There were those that opposed," Gooch said.

Cohn said he faced an onslaught of letters to the editor that cursed him and even a few derogatory and threatening phone calls.

“Why don’t I go back to Israel?” Why don’t I go back to Russia, where I came from obviously. I mean some of them just really curled your hair," he said.

The community organized a recall election for Cohn’s seat on the council. He stepped down and Cliff Brill became chairman.

However, in 1954, the Supreme Court passed the famous desegregation opinion, Brown v. Board of Education.

"The Atomic Energy Commission said it’s time to start the integration of the schools. That did not happen all at once," Gooch said. "The high school and junior high integrated and they helped change the course of history."

According to the Nashville Banner, Oak Ridge Superintendent Bertis E. Capehart announced in Feb. 1955 that 100 Black students would integrate the school system. Fifty would enroll at Robertsville Junior High and fifty would enroll at Oak Ridge High School.

Those students had a difficult task ahead, one that had never been done before in the state of Tennessee or the southeast.

The First Day

The first day at a new school can be exciting and nerve-wracking for any student.

Imagine for a moment how these students must have felt. Would they be accepted? Make friends? Some even wondered if they’d make it home safely.

There was no violence like the country would later see with the integration of the Clinton 12 in 1956 and the Little Rock Nine in 1957.

"This was a new journey, a new step. For them to behave in a way that they will be representing not only themselves but their families and the community," historian Rose Weaver said.

However, that does not mean there wasn’t a struggle.

"It didn’t come with a bombing and all that, but it wasn’t an easy transition,” said John Spratling, a coach and history teacher at Oak Ridge High School.

Weaver said the community rallied together to let the students know they were there for them leading up to the first day of school.

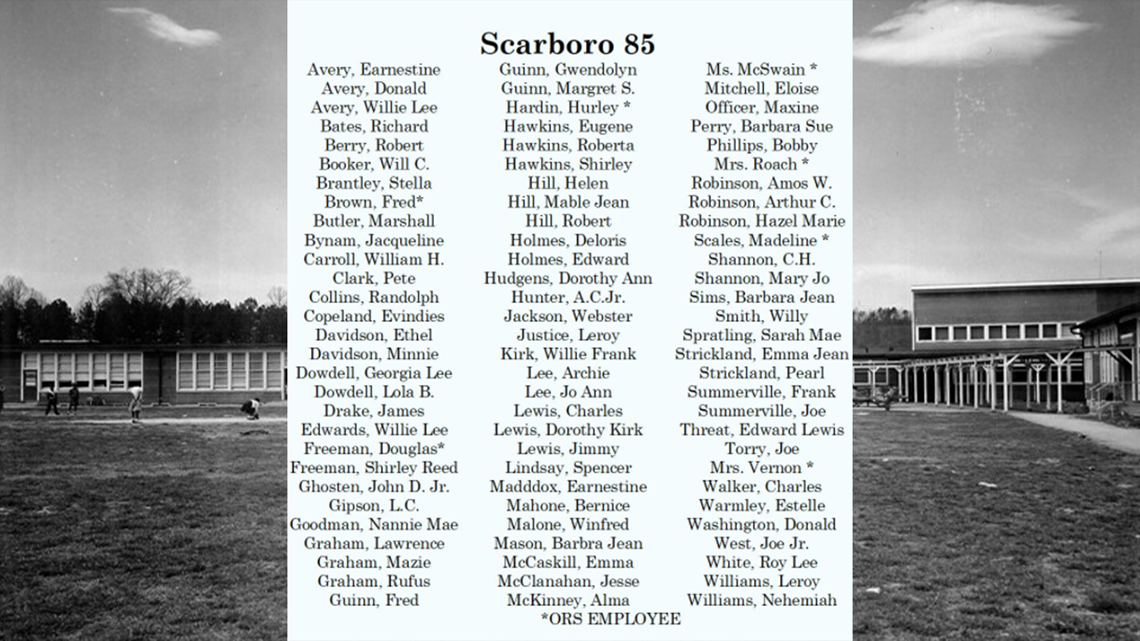

While 100 students were originally set to integrate, on September 6, 1955, only 85 Black students participated.

"Some families felt uncomfortable. Some of them were not ready. They didn’t know how they were going to be accepted," Weaver said.

Some went to Austin, the all-Black high school in Knoxville, instead. Others decided not to pursue high school and start a job. A few even went into the military.

“They were very brave young people. Remember, they were anywhere from 12 to 18 years of age," Oak Ridge Mayor Warren Gooch said. “They were thrust into this cultural change related to desegregation of schools, not at their own option, but because they were chosen to do it.”

Many of the students were given little notice of the changes coming for the next school year.

"I do not recall anyone coming to [Mrs. Arizona Officer's] class and sit down or having an assembly and saying, 'This is what's going to happen,'" said LC Gipson, one of the Oak Ridge 85. "Now you've been cast into a situation where there's approximately 1,700 students that do not want you there. So my mindset was for me to not get expelled from school."

On the other hand, in 1954, a small group of Scarboro School students who were set to attend Oak Ridge High was given the opportunity to see their new school.

Archie Lee was one of those students.

"So we had communications with some of the students before the two actually integrated," Lee said. “When I first got to high school, I had a little anxiety about how it would go.”

During the tour, Lee encountered a mixed response.

"As I was walking to the gym, there was a piece of paper that I picked up, and this piece of paper had comments on it that some of the students made. Those comments went from asking the students how they felt about integration, and some of them said it was alright with them and that we should have an opportunity as others. There was one comment that said, 'They stink,'” Lee said.

Dr. Tom Dunnigan, the principal of Oak Ridge High School, made it very clear that there would be no problems. He would not tolerate fights. He would not tolerate discrimination.

Despite the efforts of the principal and other adults, there were fistfights and other incidents.

Some students did feel isolated and afraid. Some did feel accepted.

"This is pretty heavy stuff for a young man to try and wrap his head around. To be in a school, to know that some people don’t mind that you’re there. Some people may want you to be there. But there’s a group of people that don’t want you to be there," said Archie Lee, one of the Oak Ridge 85.

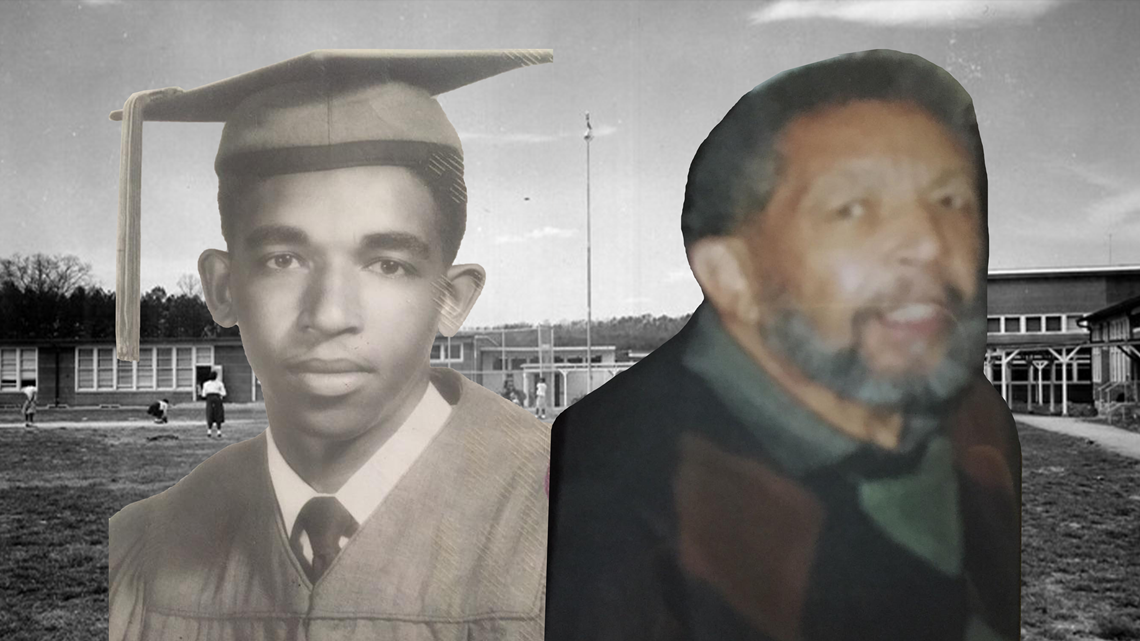

The Oak Ridge 85

85 students. 85 different perspectives. 85 unique experiences.

Many students agree on one thing, it took grit and courage to walk this path.

"It’s a lot. It was a lot. It still is for many of them. They get very emotional talking about it," Weaver said.

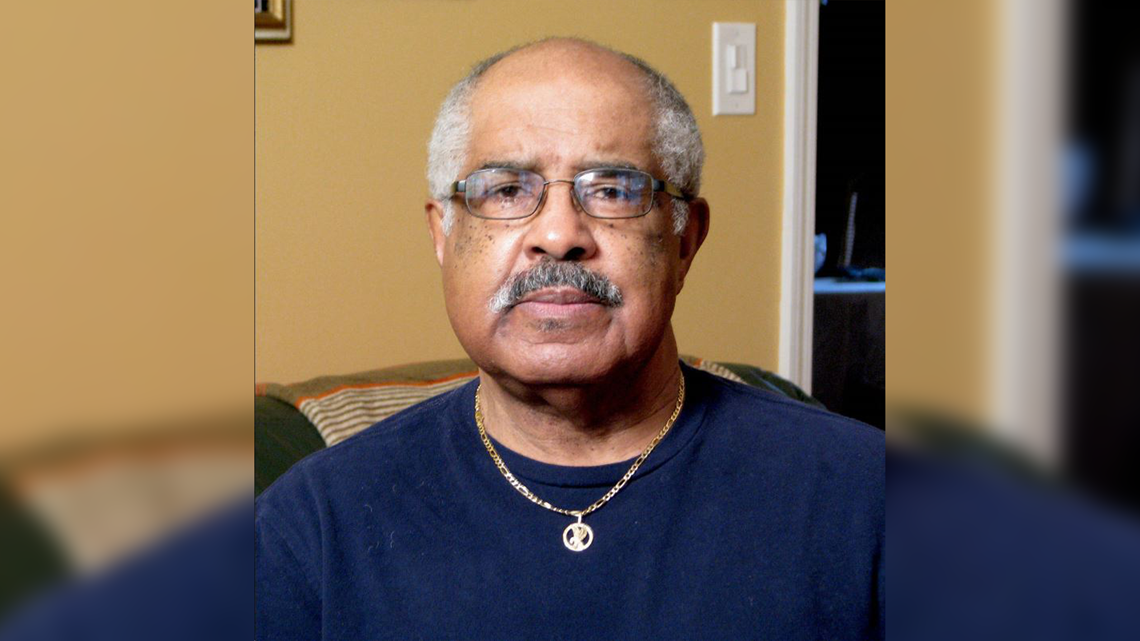

"If I could go back and do over ’55, I would greatly have preferred to stay 9th through 12th grade at Scarboro School," said LC Gipson, a member of the Oak Ridge 85 who graduated with the class of 1959.

He said during his four years at Oak Ridge High School, there was only one other Black person in his classes at any given time.

“Many teachers that may be teaching that class really did not want me there," Gipson said.

He did not join any clubs or after-school activities.

“I repeated that for four years. I got on my bus. Bus No. 18. Go to Oak Ridge High School. Get off the bus. Do the best I could. Repeat," Gipson said.

Though he made friends with his white classmates, he always had to be careful about going to their houses.

“That family that I made friends with may welcome me to their house to come study or compare notes with a classmate, but then you have to deal with the other people in the community," Gipson said.

Dorothy Lewis, another member of the Oak Ridge 85, was just 12 years old when she integrated Robertsville Junior High. She said her initial reception at the school was anything but friendly.

"They let you know, without a shadow of a doubt, that you are not welcome at their school. They weren't friendly at all," she said. "There was a lot of name-calling, jeering, just the body language, the way they would get out. They didn't want to get close to you at all."

Lewis said tensions smoothed out over time. She was able to meet some nice friends and said the teachers were great.

Historian Rose Weaver said mental battles and societal barriers were a daily reality for these students.

“There were two young men on the basketball team. They were great athletes from what I’ve been told. They set some school records, but during that time, records for Negroes were not accepted," Weaver said. “If there was an away game, the coach would call them in and say, 'Sorry guys but you’re not going to be able to go.'”

Even with the setbacks and struggles, the Oak Ridge 85 excelled academically and athletically.

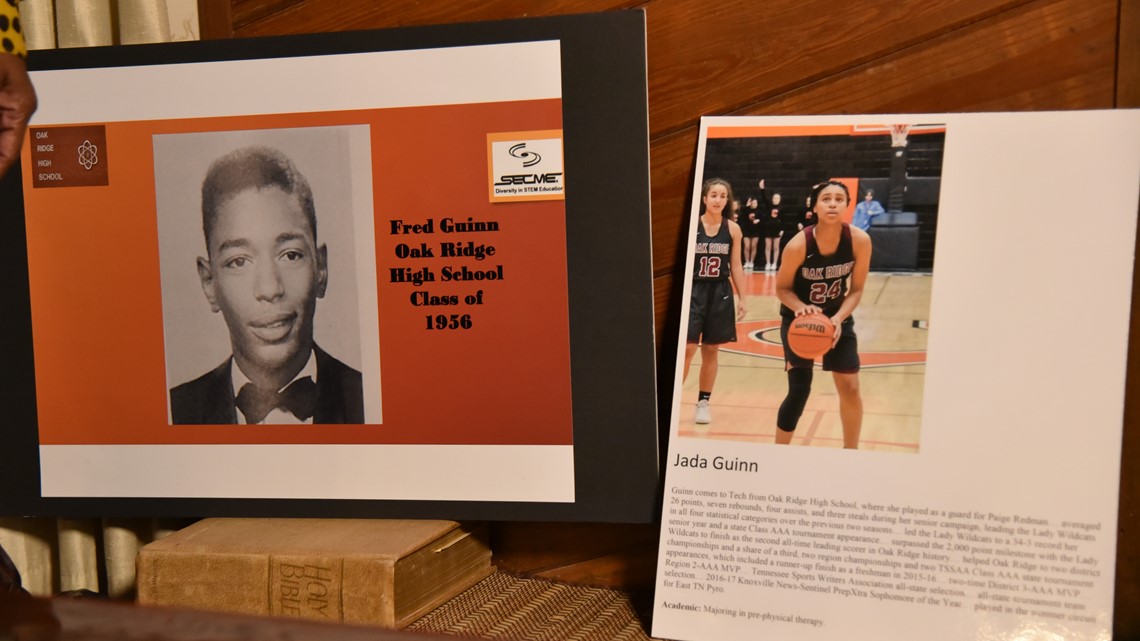

Archie Lee, who graduated with the class of 1957, was the first Black student inducted into the National Honor Society at Oak Ridge High School.

“I just thought I could do anything that anyone else could do," Lee said. “After you get to know the students in your class, they’re just classmates like everyone else. You become a student, forget what color your classmates are, and you compete. I suppose all students want to be at the top of their class. That’s what I did."

Following these 85 trailblazers, students from Scarboro School continued integrating into Oak Ridge Schools. Eventually, Scarboro School fell out of use and burned down in the 1960s.

Despite the challenges, many of the students went on to have successful careers in science, research and education.

However, for decades, their struggles and achievements were silenced.

The Secret

Oak Ridge High School and Robertsville Junior High integrated 65 years ago.

Many of you may be discovering this story for the very first time.

"We kept pushing and knocking because we asked the same questions: Why does nobody know this? Why is this such a secret?" said John Spratling, whose aunt, Sarah Mae Spratling, was one of the 85.

Oak Ridge is known to be the Secret City, but the Scarboro community believes this history should be well-known.

"It’s a hidden story," historian Rose Weaver said. "History is history, and it was unfortunate that it had not been told, as it should have been told."

Oak Ridge Mayor Warren Gooch thinks a couple of factors were involved.

The first being Oak Ridge's status as a federally created and controlled community during the Manhattan Project, instead of an official city.

"There was some confusion about well, is it a school? Is it a public school? Is it not? We kind of got lost in the crush of events that followed with Little Rock, the Clinton 12 and the integration of other facilities across the South," Gooch said.

The second part was the culture of Oak Ridge as the "Secret City." In the 1940s-60s, it was imperative not to talk about Oak Ridge for fear of exposing its atomic secrets during World War II and the early stages of the Cold War.

"I think that might be a reason but as time goes on the doors of Oak Ridge were open, and it would have been good to find out a little bit more about how integration transpired in Oak Ridge," Weaver said. "I think the primary reason is the initiative had not been taken."

Spratling points out that certain aspects of Oak Ridge's history are absent from the museums and monuments scattered throughout the community.

"Mistakes were made, it should have been more widely talked about for 40 years, 50 years," Gooch said. "This is their time. This is their story. It is long overdue, in terms of getting the recognition that they didn’t. They were always patient and hoping that they get their day."

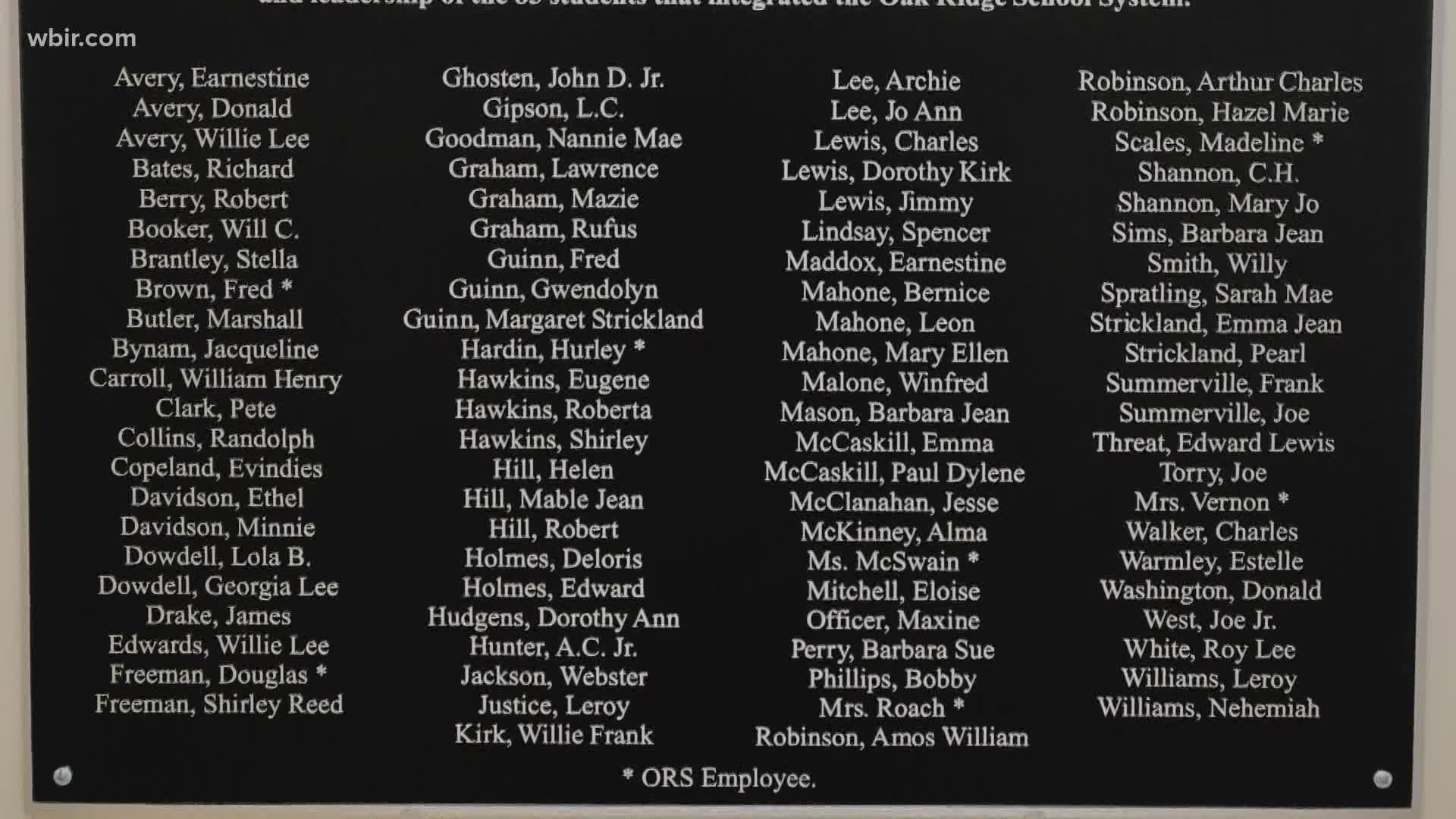

Telling history is preserving history. Only 20 to 30 students in the group are still living.

If this story is not shared, many fear it could die too. Community leaders are working to preserve this trailblazing story and last words from members of the 85.

The Future

From plaques to proclamations, this secret is finally out.

Now, community members are even more determined to cement this moment in history for generations to come.

"I think the biggest part, to begin with, was setting the tone," Oak Ridge Mayor Warren Gooch said. "So from the city’s perspective, it was including the narrative and promoting the history of the Oak Ridge 85, as a part of the ongoing story of Oak Ridge."

September 6 is now known as the Scarboro Oak Ridge 85 Day, and it was commemorated with plaques bearing the names of the 85 students going up in local schools.

"They have embraced the 65th anniversary of the integration, and that’s a step forward because, before that, they hadn’t gotten an acknowledgment," said John Spratling, a coach and history teacher at Oak Ridge High School.

Community historian Rose Weaver said the city is doing a tremendous job and wants to see the school system get more involved by adding the story of the 85 to the curriculum like the Clinton 12.

"Hopefully, we can encourage the state to get behind it and included in state history," Weaver said. "I do think it is particularly appropriate that our new pre-K school is in the Scarboro community. We all worked very hard on that."

Gooch said this new state-of-the-art facility in the Scarboro community is a bright spot because Oak Ridge was the first public school system in the state to have a pre-K.

In January 2021, the Oak Ridge Board of Education approved the renaming of the Oak Ridge Preschool to the Oak Ridge Schools' Scarboro Preschool and also approved to designate rooms inside the building in honor of Scarboro "community heroes" Arizona Officer, George Walker, Fred Brown and Sallie McCaskill with a vote of 3 to 2.

After more than 50 years, a school for young students is finally back in Scarboro, and because of the Oak Ridge 85, those future students will have an equal opportunity to learn and excel.

In February 2021, Oak Ridge announced it would add the 85 to its middle and high school curriculum and planned to petition adding them to the state education standards.

In August and September 2021, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee gave out proclamations declaring Aug. 31 as Clinton 12 and Oak Ridge 85 Day. The Oak Ridge History Museum then opened an exhibit about the 85.

If you want to learn more about the 85, the city of Oak Ridge or the Scarboro community, the following resources are available: