HUNTERSVILLE, N.C. — Two towns are desperately searching for answers after researchers confirmed higher than usual rates of cancer.

In Huntersville, a town of about 50,000 people, it’s estimated 30 residents have been diagnosed with ocular melanoma in the past decade.

Ocular melanoma is a very rare cancer that should only affect one in every 200,000 people.

"There’s one of my favorite pictures of all time, Keenan and me on her wedding day," Kenny Colbert said smiling and glancing over photos of his daughter Keenan.

"I still remember the day she called me when she said, 'Dad, they found a tumor on my eye,'" he recalled. "And I went, 'What do you mean a tumor on your eye?' And she said, 'It’s melanoma.' I didn’t dare let on to her, but my heart just sank because I knew this wasn’t good."

Keenan Colbert was 23 when she was diagnosed with ocular melanoma -- a cancer that on average affects five in every one-million people.

"We found out it’s somebody typically like me that gets ocular melanoma, it’s typically a white male and maybe their 50s or 60s," Kenny Colbert said. "The more research we did we just realized this is off the charts to have someone who is 23-years-old, female, having ocular melanoma. Off the charts."

Keenan Colbert was a fighter, though.

"She said remove my eye I don’t want any cancer cells in my body," Kenny Colbert recalled.

His daughter fought for years all the way to the end when the incurable cancer took her life.

She was 28-years-old.

But Keenan Colbert’s diagnosis and death sparked questions that would soon lead to something bigger than her family could have ever imagined.

"A few months later, there was a young lady by the name of Meredith Legg who was diagnosed with ocular melanoma," Kenny said. "And I just thought this is very freaky that we’ve got two girls that are both in their early 20s that have been diagnosed.'

Then, two more were diagnosed.

"Shortly thereafter, we found a couple of other people that lived in the area around Hopewell High School, both were in their early 30s. I said this is very strange. Now we’ve got four females who went to Hopewell High School and who lived within sight of Hopewell High School. So that kind of started Hopewell as Ground Zero."

It wasn't long before the pieces starting fitting together into a shocking, horrifying puzzle.

RELATED: Mysterious eye cancer cluster grows

"Word started traveling via social media and the next thing you know we were up to maybe 8 or 10 or 12," Kenny said. "And I said, oh wow, something is up here. We’ve now got 12 people that either lived or worked on that side of Huntersville and this is really off the charts."

And yet, there wasn't a penny from the state to investigate.

Kenny Colbert remembered a tear-filled conversation with his wife, Sue, both of them frustrated by the lack of action.

"I said until we get some people angry and until we probably embarrass a couple of public officials this is not going to go anywhere, it’s going to take people in our neighborhood to demand action."

And, he said, that's exactly what happened.

"People got mad. People got scared, and people got mad," Kenny said. "People were saying this could be my kid. I’ve got a 10-year-old and we don’t know where this is coming from or the cause."

RELATED: NC bill filed would put $100,000 toward solving Huntersville ocular melanoma cluster mystery

Once more than a dozen confirmed cases of ocular melanoma were identified in Huntersville, the state passed a bill allocating $100,000 to investigate.

That was April 2017. In the two years that followed, the number of cases doubled. In October, the grant money ran out.

The results of the investigation were shared with a packed room. Two years of geospatial research, genetic testing, and soil testing, turned up nothing.

And then, there was a comment from Dr. Michael Brennan, a retired ophthalmologist who has been heading the studies.

It was so quick, you might have missed it.

"I’ve talked with four new patients," Dr. Brennan said at the meeting.

If those additional four patients are confirmed, the potential case total would now be 30. Thirty people in this town of about 50,000 have one of the world’s rarest cancers that should only affect one in every 200,000.

"They told us, hey, we’ve done this testing and it’s inconclusive, oh, by the way, there’s four new cases," said Rob Kidwell, multi-term commissioner for the town of Huntersville.

“We can’t say it’s inconclusive or there’s nothing connecting it and then say there’s four more cases," Kidwell said. "There’s something there. We have to look for it.”

It's been two years with no answers and no more money.

"Right now, there’s no new testing scheduled?" NBC Charlotte Defender Savannah Levins asked Kidwell.

"No," he responded. "No."

But that isn’t the end of this story.

Because just down the road in the neighboring town of Mooresville, another mystery is unfolding.

This part of the story starts with Taylor Wind.

"She developed a lump on the side of her neck they said it was swollen gland probably and I shouldn’t even worry about it," her mom said.

Susan Wind said, eventually, she pushed for more tests.

"Seven weeks later, we got a diagnosis that she had thyroid cancer, and it had spread throughout her whole neck," she said.

Taylor Wind was just 16. She had thyroid cancer. Doctors had to slice open her neck to remove it.

"As soon as we put her story out there, people started contacting me," Susan Wind recalled.

"Neighbors on my street came to me, and they were like, we have thyroid cancer. Other moms in the area and other neighborhoods were contacting me saying my daughter got thyroid cancer, kids as young as 13 years old."

Susan Wind started making maps and keeping track. And she started wondering if this wasn’t all a coincidence.

"I asked our doctor, 'Is this normal? That there’s three thyroids cut out on my street?" And she said that doesn’t sound right," she said.

But Susan Wind didn’t want to wait around for the state to allocate research money. She’d seen how slow things moved in Huntersville.

Susan Wind raised over $100,000 to pay independent researchers at Duke University to investigate. The first thing the team did was validate her fear.

"They confirmed we had a thyroid cancer cluster," Susan Wind said.

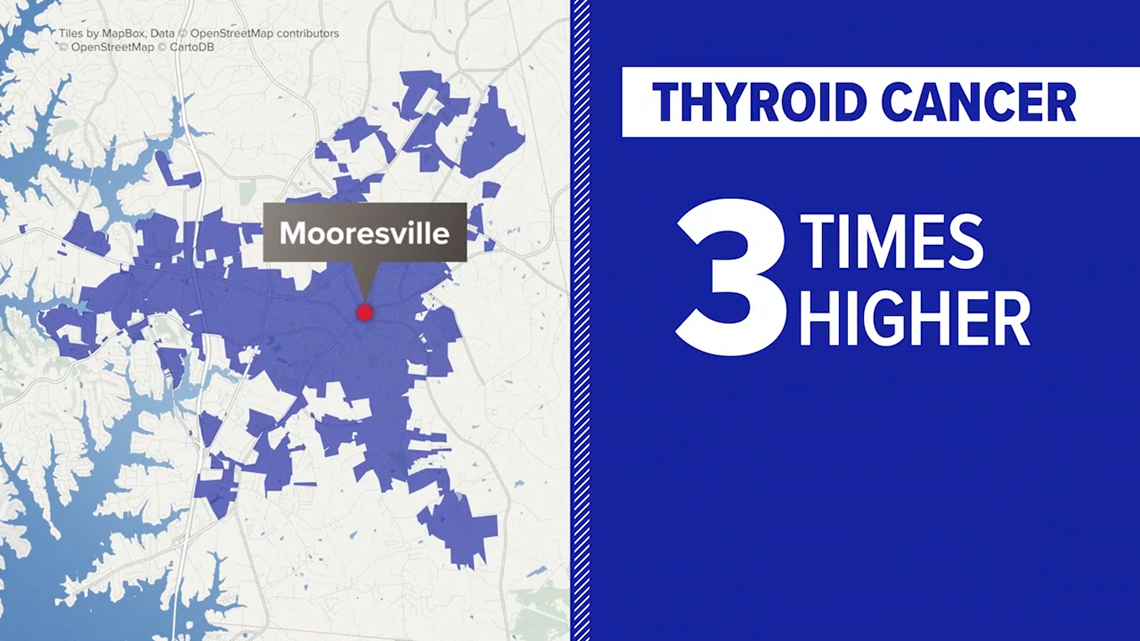

The researchers pulled state data from 2012-2016 and found 191 cases of thyroid cancer were diagnosed in Mooresville, a lake town of about 40,000.

Right down the road from an inexplicable cancer cluster was another one.

The thyroid cancer rate in Mooresville determined to be three times higher than normal – condensed mostly in zip codes 28117 and 28115.

"There’s so many, and nobody connected the dots before Susan that something was wrong," said Trisha Edmiston, who was diagnosed with thyroid cancer in January.

"When you start walking through a neighborhood and you’re like, 'They have cancer, they have cancer, they have cancer,' there's got to be something wrong," she said.

"There’s dogs and cats that have thyroid cancer in this area. You realize somethings going on."

Just like in Huntersville, many of the patients are young girls, like Kathryn Canlas, who was diagnosed at just 13-years-old.

"There are days when I just cry," Canlas admitted. "I just had to have surgery again for the second time. It’s harder now because I’m 25 so I have bills to worry about."

She's a nursing student working two jobs. As she recovers, she's shocked to learn she’s not alone -- not by a long shot.

"There could be something here affecting all of us and it actually happens to a lot of us," she said. "I'm angry and I want answers."

You can’t miss the rows of for-sale signs dotting the towns. And maybe you can’t help but wonder if it’s a coincidence.

"We’ve been here in Mooresville 17 years," said Danielle Bulger, mom of three young boys.

She was diagnosed with thyroid cancer last year.

"Do you feel safe living here?" Levins asked.

"Well, I did," Bulger said, pausing with a sad smile.

"It’s either we’re going to stay and fight to get answers or we’re gonna pack it up and move somewhere else."

She sees the signs that something is wrong.

“On my street alone, there’s three of us," she said. "They’re testing everybody’s soil and air and slowly but surely it seems like it’s all connected."

But how? If something is causing these cancers – what? And why are families who live here just now learning about it?

"The health department had all of this data, and you think they would let doctors know so that when people like me bring a kid to the doctor with thyroid symptoms would automatically do a blood test," Susan Wind said.

But there are no answers to those questions. Not yet.

"It’s just been kind of swept under the carpet and people continue to be diagnosed," Bulger said. "There’s always a new phone call a new patient a new diagnosis. I think until it happens to you directly it’s really easy to ignore."

It’s getting harder to ignore, though. The anger, the fear, the growing numbers.

"It really appeared as though we had an issue on our hands that we have a cancer cluster in Mooresville," Mooresville mayor Miles Atkins said.

STAY INFORMED: Sign-up for our newsletter

“Nobody else is doing any kind of a study," Atkins said. "A private citizen has to raise $100,000 to figure out what made her daughter sick and was happening in the community but there were no state dollars no other funding available to understand well what’s taking place."

He believes something is wrong.

And he knows saying so won’t always be popular among the constituents in this town he represents and loves.

"I understand people are concerned about their home values," he admitted. "But we cannot stick our head in the sand and say there’s not a problem. We need to acknowledge that there’s concerns, that we do have a problem, and then we have to find the answers."

The Duke University researchers, still using the grant money raised by Susan Wind, identified and interviewed patients. They tested their environments, their genetics. They tested the town’s water. They tested schools for radon.

The researchers did find elevated levels of Radon in the homes of three cancer patients in Mooresville. According to the EPA, radon comes from the natural breakdown of uranium in soil and can make its way into homes and buildings.

And then, all eyes locked on the elephant on the lake.

And then, all eyes locked on the elephant on the lake -- Duke Energy’s Marshall Steam Station and the 17 million tons of coal ash sitting there in an unlined basin.

"The natural instinct would be the correlation between, well we have all this coal ash, it can be toxic, and then does it have some correlation to this cancer?" Atkins said. "It’s like, well what else can it be?"

Duke Energy spokesperson Paige Sheehan agreed to sit down with Defender Savannah Levins to answer those questions.

"Is coal ash toxic?" Levins asked.

“No," Sheehan responded.

"If I had a bottle of water here and I would drink a bottle of water that water is perfectly safe for me. If I were to drink 50, that water would be toxic because it’s the dose and exposure that makes it toxic. Coal ash is not toxic any more than a bottle of water is."

"Wait, isn’t it a fact that heavy metals and some carcinogens are in coal ash?" Levins responded.

"Yes, and they’re also in soil and naturally occurring," Sheehan responded.

In April, the department of environmental quality ordered Duke Energy to close and fully excavate any and all remaining impoundments of coal ash, citing public health concerns.

Duke filed an appeal, asking instead to cap the ash in place, saying that would be both safer and more cost-effective than moving it all to another location.

A few months later, the utility company lost that appeal.

Editors note: Duke Energy says their appeal that the DEQ’s decision was not supported by scientific evidence has not yet been addressed in court. Therefore, a final determination has not yet been made.

Meanwhile, they maintain the ash is not harmful to the people who live nearby.

"If coal ash is the same as dirt or water, why are state agencies like the DEQ and federal agencies like the EPA requiring that they be closed, capped, excavated?" Levins asked.

"I’m not suggesting that coal ash is the same as water," Sheehan responded. "I’m saying when you look at toxicity it’s about dose and exposure. There is a component in coal ash, arsenic, that is a carcinogen. somebody would have to have a very high exposure rate over a very long period of time, like inhaling it for example, before they might face a health concern."

Duke Energy says no, the coal ash in this basin is not lined as current laws would require – but they say it is closely monitored.

"It’s not in the air soil or water in any measurable way," Sheehan said.

But let’s go back a few decades before coal ash and its potential health concerns made headlines.

Records we uncovered from the DEQ show coal ash from the plant was once sold as construction material. People could pick it up by the truckload and bring it home to use as foundation, dirt, etc.

"Was there a time that people could pick up coal ash and use it as construction fill?" Levins asked Sheehan.

"Yes," Sheehan responded. "Back in the 1990s in the early 2000s as our community was booming there was an interest in using coal ash as a structural fill. Duke often sold or marketed through a third-party coal ash to outside folks who wanted to improve their property. It was acceptable and regulated by the state."

But that realization hit residents hard. Records show the ash was integral to the construction and housing booms in both Mooresville and Huntersville.

"A lot of this cold ash was used, do we know where all of it went?" Levins asked Mayor Atkins.

"We don’t, we honestly don’t," he replied. "Because at the time it was legal to sell it or use it. We’ve been living among structure fill and coal ash for decades."

Enter newly elected state senator Vickie Sawyer.

"The coal ash management act does allow for a certain percentage of coal ash to be used as beneficial fill is what they call it," Senator Sawyer explained. "And I just felt like that shouldn’t be in our environment."

Even though Duke Energy says they don’t sell coal ash for construction anymore, Senator Sawyer filed a bill last session that would have officially banned the practice statewide.

"That bill did not go anywhere," she admitted. "I think it honestly just died because I didn’t have enough horsepower as a freshman young senator to get it moving.”

Besides, she says, the basins were being ordered to close anyway.

RELATED: Scientists: No coal ash found in Iredell County drinking water, but more research needs to be done

And Duke Energy says the bottom ash used for those projects contains less than 1% of trace elements like arsenic.

But still. People began to wonder.

The Duke University researchers have now begun testing the soil around schools in the area that were built around the time coal ash was commonly used for construction.

And they started asking questions of the men and women who transported and used it back then.

"Landscapers came to me they said, 'Yeah, I have cancer,'" Susan Wind said. "It was mixed with topsoil and put over hundreds and hundreds of lawns all throughout Lake Norman.”

The DEQ kept records of where the largest amounts of ash went – anything over 10,000 cubic yards was noted.

Duke Energy says they only have 21 records of coal ash being used for what they consider to be smaller projects, averaging 50 cubic yards.

Keep in mind, 50 cubic yards equals about 90 thousand pounds.

"Folks who were building homes and gardens sometimes they could go up and grab a truck full of coal ash for smaller uses, those were not documented," Senator Sawyer said.

She admits she’s not sure what to think about that, but she’s hesitant to say it’s what’s causing the cancer.

"I’ll be honest when I first started looking at all of this, I thought that was absolutely the boogie man in the room," Senator Sawyer said.

"I was very convinced the coal ash is contaminating all of Mooresville. It’s easy to make that assumption, but you cannot prove it. What kind of legislator am I being if I purposefully mislead people when I truly don’t know the answer myself?"

Although coal ash contains toxic substances like arsenic, lead, and mercury, there has been no research directly linking coal ash to thyroid cancer or ocular melanoma.

But people who live here, people who are getting sick, argue there haven’t been any studies that officially rule it out, either.

"I asked scientists all over this country including the ones at Duke University I said is this safe?" Wind said. "And they say no, it should be treated as hazardous waste; it’s loaded with toxic chemicals. So I mean, is that what caused all these cancers? We can’t say that. But until the state proves that I can have my kids rolling around with it in the yard and there is no way this could be linked through ingestion or inhalation, could’ve caused anyone’s illnesses in that town, I’m not going to take the utility companies word for it."

"Are you 100% certain that the coal ash has no link to any of those cancer cases?" Levins asked Sheehan.

"Scientific evidence and medical research tell us there is no connection between coal ash and thyroid cancer or ocular melanoma," Sheehan responded.

"I wasn’t aware of any third-party study that definitively said there’s no way coal ash causes cancer," Levins replied. "Am I wrong?"

"I can tell you coal ash does not cause thyroid cancer or ocular melanoma," Sheehan said.

“The Department of Health and Human Services looked at this extensive body of research and concluded “no published studies support an association between coal ash exposure and thyroid cancer,” Duke Energy spokesperson Bill Norton later clarified.

“Also, the Huntersville ocular melanoma task force studied Riverbend, our retired plant, and concluded the “’metals [in coal ash] are not considered relevant to uveal melanoma.’”

"We still need to consider that as a hypothesis," Senator Sawyer said. "But that can’t be our only hypothesis because we’re going to skew the results."

But many people living in these clusters say they want to know for sure.

"It’s shocking and nauseating," Bulger said of Duke Energy's response to the issue. "We have a water filter and I haven’t gone on the lake since I’ve been diagnosed. I don’t want anything to do with it quite honestly."

The people affected say the fact that there are two apparent cancer clusters in our great state, in neighboring towns, is something that shouldn’t be ignored.

"It is uncanny right to have all these things in the same general region," Senator Sawyer said. "I think would be shortsighted not to look that there is a connection."

If you still wonder whether this is all just a sad coincidence, consider Steve Durant.

"I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer in 2010," he said.

"And then in 2017, I was diagnosed with ocular melanoma."

He was diagnosed with both cancers while living smack in the middle of the clusters.

"To have two clusters of different cancers within a 2-town radius should be very alarming for a lot of people," he said.

"There’s got to be something. You’ve got a put 2 to 2 together that there’s something environmentally something in that area that would cause so many people to get this."

He says he worries now, too, about the coal ash used for construction of the two towns.

"My wife loves to garden. we put flowers in and vegetable beds and I can remember digging in the back and coming across this gray dust in the soil," Durant recalled.

"And at the time I was like, well, I guess this is North Carolina soil. And I wonder now, was I digging in coal ash that was laid as a foundation underneath the subdivision I was in?"

Thanks to the $100,000 from the state, and the $100,000 dollars Susan Wind raised, investigators in both towns have ruled some things out.

The Duke University team determined coal ash is not poisoning anyone’s well water. In 2016, Duke University researchers released a study showing the presence of hexavalent chromium in several wells in the state. It was noted in the study the presence of the carcinogen was not linked to coal ash. They tested all schools in Iredell County for radon, and everything came back normal.

The task force investigating the ocular melanoma cases in Huntersville didn’t find any genetic cause or common denominator among patients’ day to day lives.

They tested some soil around town and near Hopewell High School and found nothing alarming and no obvious traces of coal ash.

But the biggest frustration, the overwhelming fear, the dark cloud hanging over these two towns, is the not knowing.

In Huntersville, there’s no more money to continue research.

In Mooresville, some grant money is left, and Sawyer helped pass a law this year that directs the NC Policy Collaboratory to assemble a research team to gather more data.

But those for sale signs are still up.

"A lot of people are packing up and moving they’re scared," Edminston said.

And people are still being diagnosed.

"Everybody’s busy with their own lives, and until it hits you it doesn’t sink in," Durant said.

"But somehow, we’ve got to get the word out more and get more research done. If it is environmental, nobody’s gonna say, hey, I did it, it’s my fault. So we’re gonna have to do the hard work to do research and get the state involved."

The state health department says they’re monitoring the situation and have made formal recommendations for more research to be done.

"It honestly just boils down to money," Atkins said.

But so far, state legislators have not approved a penny more.

(Editor's note: Senate Bill 277, which would allocate $100,000 to Huntersville to continue research into the ocular melanoma cluster, was approved to be added into the state budget. Senator Natasha Marcus of district 41 sponsored the bill, and tells WCNC NBC Charlotte she is hopefully will pass despite the Governor’s veto which was still in place as of this story’s publication, 11/25/2019.)

"They don’t care because it hasn’t happened to them, but it could happen to them if answers aren’t found out," Canlas said.

"It could happen to anybody."

A bill that would have given Huntersville researchers another $100,000 grant never made it past committee.

"Managing expectations of how government works is the worst message I have to send," Senator Sawyer said. "That it does take a long time, that there are no answers right now, that we are continuing to fight. And if I do find that one smoking gun I will not stop until it’s rectified. It’s just finding that answer is the struggle and the hard part right now."

"If there’s so much confidence that the coal ash has nothing to do with these cancer clusters, why not get Duke involved with these studies?" Levins asked Sheehan. "Why not donate to these grants? Why not be on these boards?"

"I think the very best place that we can and have been spending our resources is to ensure that our operations are protecting people and the environment," Sheehan said. "I can’t imagine what these parents are going through but that’s why it’s important for us to acknowledge that emotion, and then we have to ask that there be room in the discussion for the facts."

Still, one fact remains above all else.

If something is sickening, killing people in Huntersville and Mooresville, no one knows what it is.

"We just need more funding so we can get those studies moving and continue to move so we can find out an answer," Senator Sawyer said.

For now, here’s the plea from two towns:

Care.

Care that your neighbors are dying.

Care that they don’t know why.

Care that it could be you, or your friend, or your child.

“Hopefully another mom or dad will wake up one day and say I need to do something," Wind said.