MECKLENBURG COUNTY, N.C. — Charlotte looked a lot different for a young Helen Kirk.

"When I was small, there was a lot of segregation that I didn’t realize because my family kind of hid me from it," Kirk said. "You couldn’t go downtown and eat. Separate bathrooms for Black and white."

Now, she’s 94 years old.

She’s lived in west Charlotte for decades. It’s an area where conversations of real estate and development haven't always included people like Kirk.

"We lived over near Oaklawn Avenue, and they bought all of that because they were going to build I-77," Kirk remembered. "So, that meant that we had to move. So, we were displaced that way, and we left there, and we came here."

Here, in the shadows of Charlotte’s growing skyline, home values have soared. It's under this very skyline where banks and the federal government redlined Kirk’s quaint home.

"Here’s the wedge of wealth going southward, and here’s the crescent of much less wealth," historian Tom Hanchett said, gesturing to maps of the Charlotte area.

It’s a shape Charlotteans find familiar.

Redlining is just one of the many policy decisions that were made throughout the 20th century that helped some people and didn’t help other people.

For decades, Hanchett has taken deep dives into issues impacting Charlotte as a fast-growing metro — specifically those issues surrounding both racial and economic segregation.

"I’ll give you an example," Hanchett started. "If you look at the redlining map, Dilworth Road was green and blue -- high quality -- much of the rest of the neighborhood was blue, yellow: 'Be cautious banks.' And then you go down to South Boulevard, that area was solid yellow: ‘Banks, you probably don’t want to give out loans to homeowners.'"

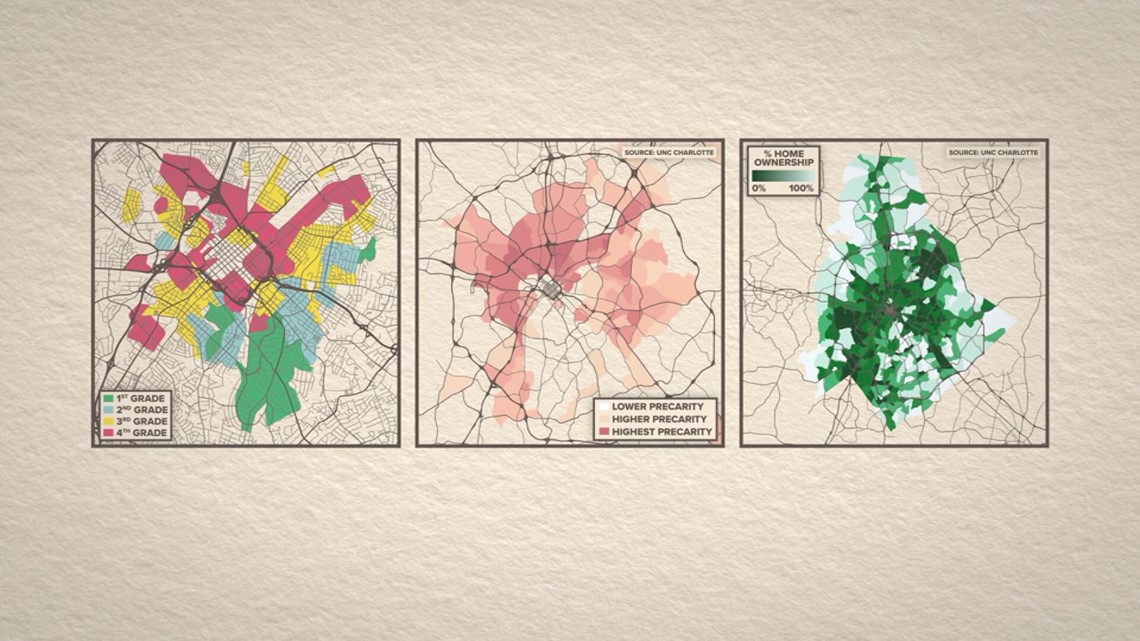

These are three maps of the Charlotte area.

The first is a redlining map from the 1930s, where the federal government decided those red and yellow sections, home to non-white neighborhoods, were risky too invest in.

It's followed by a more current map. The dark orange in that map shows where people are at the highest risk for losing their homes.

WCNC Charlotte is always asking "where's the money?" If you need help, reach out to WCNC Charlotte by emailing money@wcnc.com.

Finally, on the third map, the dark green is where the least amount of people own their homes. The areas outlined are all the same location -- where federal government considered predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods as undesirable, pushing investors and funding to white neighborhoods instead.

"And so there’s a lot of beliefs that are passed on, people like to live in this area, this is a good area to do business," Hanchett explained.

That’s where policy stepped in. The Fair Housing Act made race-based redlining illegal, while community reinvestment directed banks to invest in all areas of a community.

But those pieces of policy are decades old. Hanchett believes there are solutions that might work now.

"Putting together some policy group, some unit of government who takes on that cause takes ownership of it, could be a powerfully good thing," he offered.

It could potentially even help keep Kirk in her neighborhood, and help others like her.

"I hope so," Kirk said. "I hope so."

Contact Kia Murray at kmurray@wcnc.com and follow her on Facebook, X and Instagram.