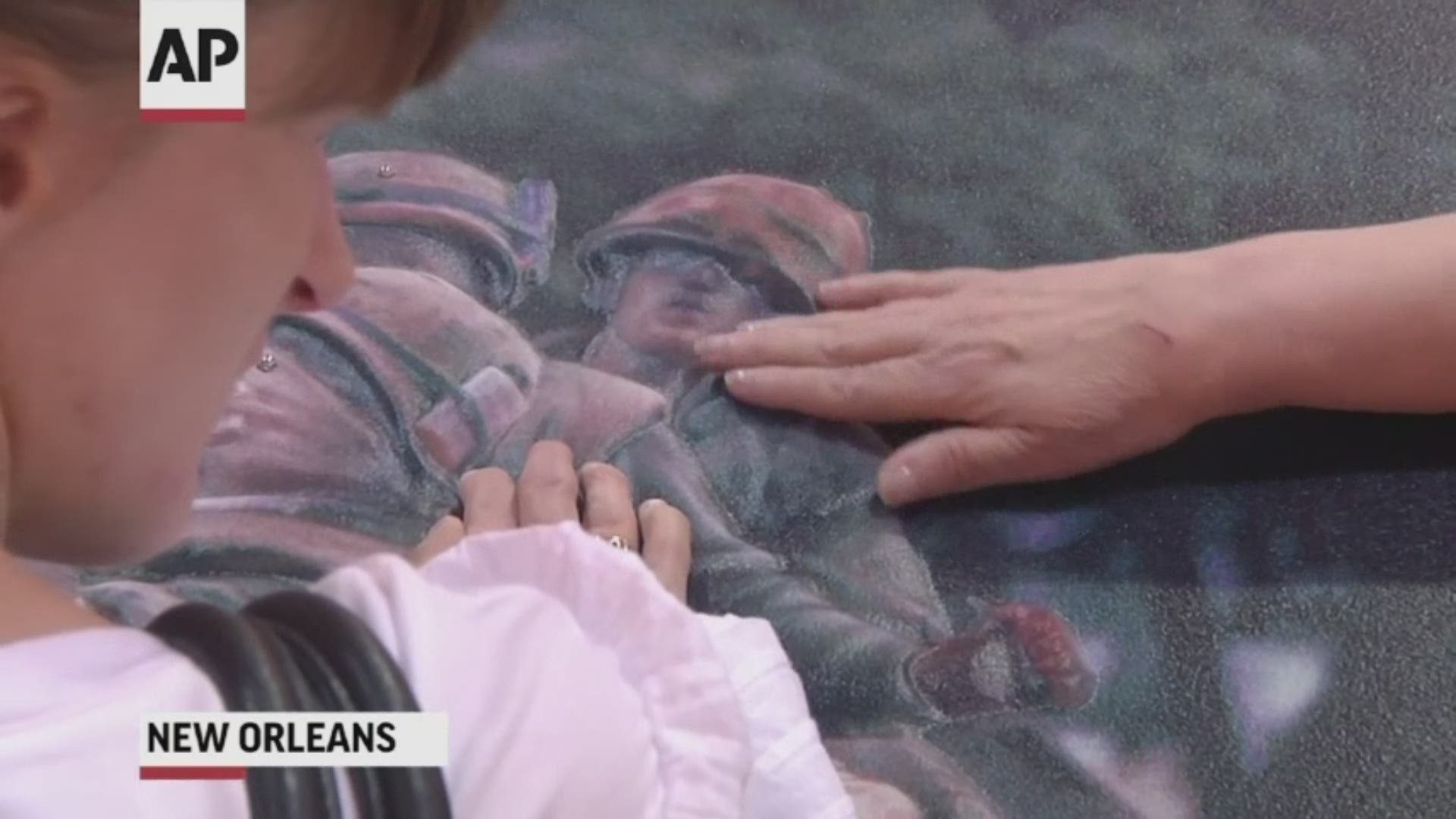

NEW ORLEANS — As people at the American Alliance of Museums' trade show passed their hands along the raised figures in touchable versions of a Vietnam War photograph, small metal sensors touched off recordings to explain whose picture they were touching and what had happened to him. At a nearby booth was a flat reproduction of a Van Gogh self-portrait with slightly raised, slicker areas to show both outlines and how brush strokes swept or swirled within those outlines.

Museums nationwide are working to make their collections more accessible for people with disabilities, said Elizabeth Merritt, vice president for strategic foresight for the alliance, which represents museums of all sorts, from tiny local history museums to huge zoos. Hours when lights and noise levels are kept low for people on the autism spectrum are another example of inclusiveness, she said, as are websites and smartphone apps designed to work with screen readers for the blind.

RELATED: Blind tattoo artist defies odds

Not all touchable art is high-tech. The Singapore Art Museum commissioned three artists to make touchable adaptations of their own works, and plans more.

3D Photoworks of Chatham, New York, was created by photographer John Olson to make his work and other two-dimensional art accessible to the blind and visually handicapped. The company has digital artists carve out contours for scanned art. After the models are created, small metal sensors are added to trigger narrations about the work and the figures within which they're set.

"I've never seen anything like that, where it integrates touch and sound," said Sophie Trist, 22, who has been blind since birth.

Her favorite among three art works and a map was Romare Bearden's collage "Three Folk Musicians," showing two guitarists and a banjo player.

Without audio, she said, "I wouldn't have been able to tell the difference between a guitar and a banjo. ... Whereas if it were only the sound, it wouldn't be the full picture, either." She appreciated hearing the banjo and learning that it was invented by enslaved Africans.

Trist, a resident of suburban Mandeville, Louisiana, and a rising senior at Loyola University of New Orleans, was among several members of the National Federation for the Blind with Olson, who has partnered with the federation for about a decade.

Other high-tech adaptations noted by the alliance are 3-D models made by the Brooklyn Museum for the "sensory tours" it has held for years for blind or partly sighted patrons. That museum also offers tours with headsets to amplify the guide's comments as well as tours in American Sign Language. In Claremont, California, at the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology , described on its website as the only nationally accredited U.S. museum on a high school campus, students can scan fossils and create models of them.

The Louvre commissioned small low-relief models of parts of its exterior for exhibits about the museum's own eight-century history, said Philippe Moreau of Tactile Studio 's Canada office, which did the work.

The studio's many displays, diagonally across from Olson's at the AAM expo, included one such model; the Van Gogh reproduction; a copy of a bust by French artist Jean-Baptist Carpeaux; and, from work for the Louvre of Abu Dhabi , a line drawing taken from a painting in a sacred Hindu text. It shows the buffalo demon Mahishasura fighting the many-armed goddess Durga. The outlines are in slick, slightly raised plastic, with text and Braille labels including "Sword and shield," ''Arrows" and "Leaping lion" — the animal on which Durga is riding.

Though created to give blind and visually handicapped people a look at flat art, the works also offered a new view to the sighted.

Court Myers, a technical consultant for the American Indian Cultural Museum in Oklahoma City, ran his fingers across a set of "brush strokes" in Tactile Studio's Van Gogh.

"Wow!" he said. "You go up to his 'Starry Night' and want to feel what those swirls look like."

He was also blown away by "The Tank" — a 4-foot-wide blowup of Olson's famous photograph of wounded Marines getting emergency treatment on top of a tank during the Tet offensive in February 1968. The sensor for a Marine shown holding a wounded man invoked an interview in which he explained why he had a toy squid in his helmet band.

The combination of hearing, touch and sight changed the sensation itself, Myers said: "For a second there, it felt squiddy."