WASHINGTON — Heart inflammation is uncommon in pro athletes who’ve had mostly mild COVID-19 and most don’t need to be sidelined, a study conducted by major professional sports leagues suggests.

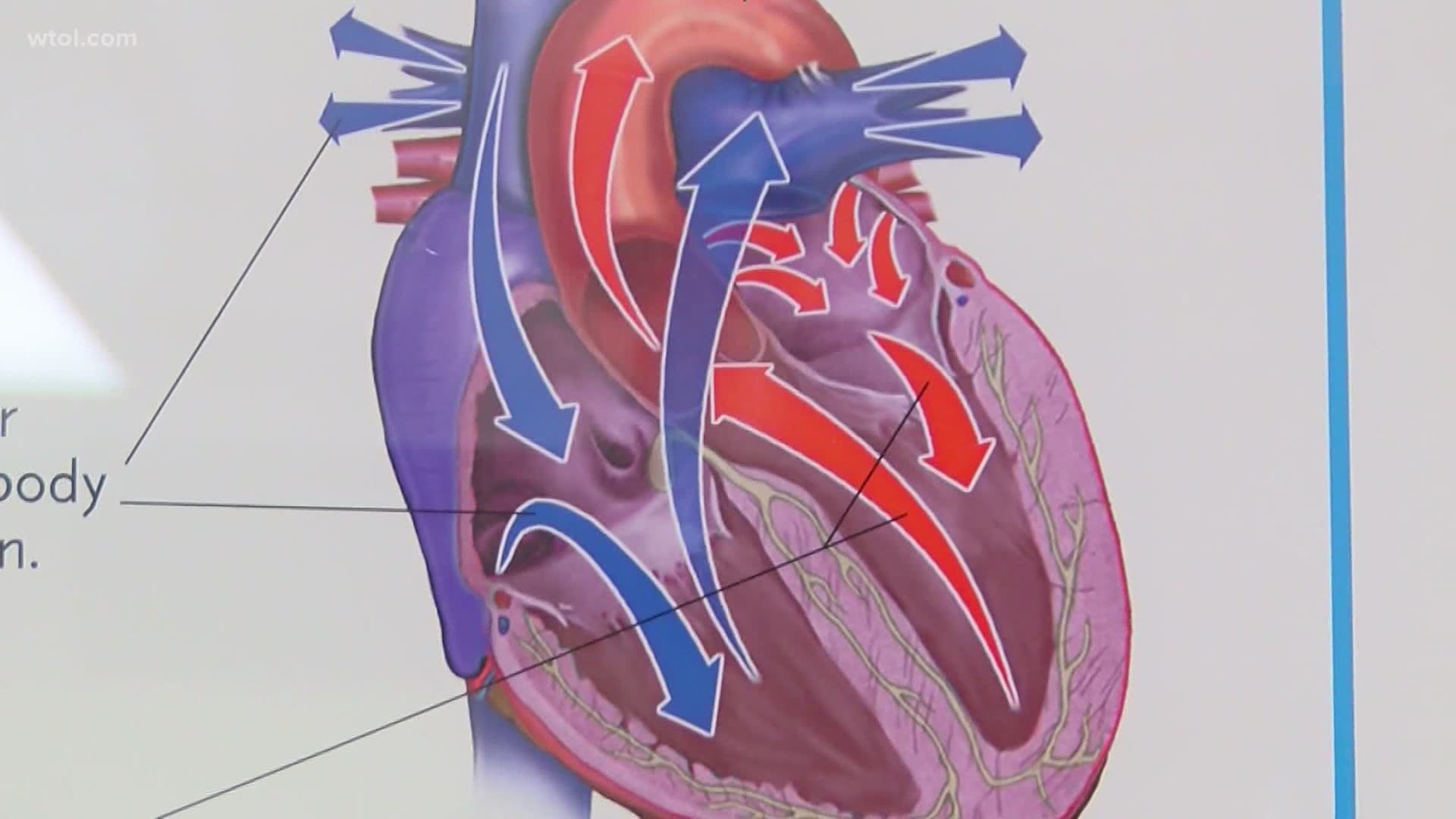

The results are not definitive, outside experts say, and more independent research is needed. But the study published Thursday in JAMA Cardiology is the largest to examine the potential problem. The coronavirus can cause inflammation in many organs, including the heart.

The research involved professional athletes who play football, hockey, soccer, baseball and men's and women's basketball. All tested positive for COVID-19 before October and were given guideline-recommended heart tests, nearly 800 total. None had severe COVID-19 and 40% had few or no symptoms — what might be expected from a group of healthy elite athletes with an average age of 25. Severe COVID-19 is more common in older people and those with chronic health conditions.

Almost 4% had abnormal results on heart tests done after they recovered but subsequent MRI exams found heart inflammation in less than 1% of the athletes. These five athletes all had COVID-19 symptoms. Whether their heart problems were caused by the virus is unknown although the researchers think that is likely.

They were sidelined for about three months and returned to play without any problems, said Dr. Mathew Martinez of Morristown Medical Center in New Jersey. He's the study’s lead author and team cardiologist for football's New York Jets.

Two previous smaller studies in college athletes recovering from the virus suggested heart inflammation might be more common. The question is of key interest to athletes, who put extra stress on their hearts during play, and undetected heart inflammation has been linked with sudden death.

Whether mild COVID-19 can cause heart damage ‘’is the million-dollar question,’’ said Dr. Richard Kovacs, co-founder of the American College of Cardiology’s Sports & Exercise Council. And whether severe COVID-19 symptoms increase the chances of having fleeting or long-lasting heart damage ‘’is part of the puzzle,’’ he said.

Kovacs said the study has several weaknesses. Testing was done at centers affiliated or selected by each team, and results were interpreted by team-affiliated cardiologists, increasing the chances of bias. More rigorous research would have had standardized testing done at a central location and more objective specialists interpret the results, he said.

Also, many of the athletes had no previous imaging exams to compare the results with, so there is no way to know for certain if abnormalities found during the study were related to the virus.

’’There is clearly more work to do but I think it is very helpful additional evidence,” said Dr. Donald Lloyd-Jones, president-elect of the American Heart Association.

Dr. Dial Hewlett, a member of a COVID-19 task force at the National Medical Association, which represents Black physicians, said the study ‘’is extremely timely.’’ Hewlett is a deputy health commissioner for New York's Westchester County and advises high schools and colleges on when to allow young athletes to return to play after COVID-19 infections.

‘’I’m grateful that we are starting to get some data to help guide us in some of our decisions,’’ Hewlett said.