UVALDE, Texas — Bullet fragments lodged in the children's arms and legs. Traumatic flashbacks flooding their nightmares. For the 17 people injured during a mass shooting last week in Uvalde, Texas, healing will be slow in a community mourning the deaths of 21 others.

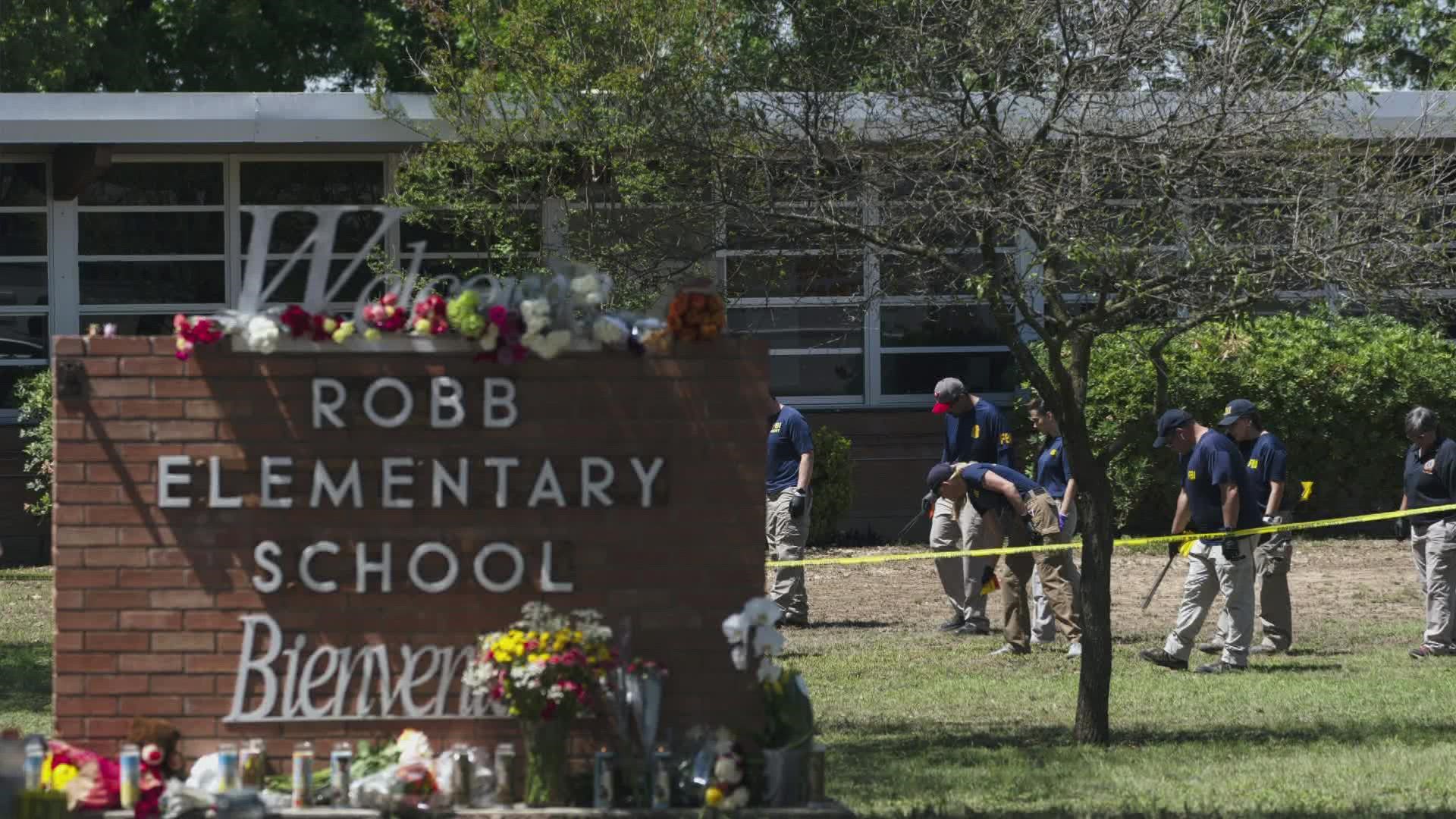

As the tight-knit town of 16,000 holds funeral after funeral and investigators examine how police responded to the shooting at Robb Elementary School, several of the victims are still in hospitals over an hour's drive away in San Antonio, undergoing treatment for bullet wounds.

Uvalde Memorial Hospital, which treated 11 children and four adults in the hours after the shooting, discharged 10 of those patients the same day and transferred five to San Antonio hospitals. The grandmother of the shooter, who was shot in the face before the 18-year-old gunman entered the school, was also hospitalized. On Wednesday, the San Antonio hospitals were still treating five patients, with one 10-year-old girl in serious condition and the rest deemed to be in good condition.

Among the injured were several fourth-grade students whose classmates and teachers were shot to death. One young survivor, 11-year-old Miah Cerrillo, told CNN that she and a friend used her dead teacher’s cellphone to call 911 and waited for what felt like hours for officers to arrive. Miah, who suffered a bullet fragment to her back, said she covered herself with a friend's blood and pretended to be dead.

“We’re just taking it day by day,” the girl's father, Miguel Cerrillo, told The Associated Press in a brief phone interview Wednesday.

The family is raising money for Miah's medical expenses to treat both injuries caused by the bullet fragment and the mental trauma of surviving the shooting. Cerrillo said that while his daughter is now at home, she has not opened up to him about what happened in the classroom.

The long-term devastation of the shooting on those who were closest to it hung heavily on their family members this week as they put together fundraising campaigns to help pay for their treatment.

Noah Orona, 10, was “trying to comprehend not only his wounds, but witnessing the suffering of his friends, classmates, and his beloved teachers," his older sister Laura Holcek wrote on a GoFundMe page for his treatment.

Orona had been struck in the shoulder blade by a bullet that exited his back and left shrapnel in his arm, the Washington Post reported.

Family members of 9-year-old Kendall Olivarez posted in another fundraising campaign that she would need several surgeries after she was shot in the left shoulder and hit by fragments of bullets on her right leg and tailbone.

Her uncle Jimmy Olivarez said Wednesday that Kendall was doing “OK."

Yet the mental wounds from the shooting rippled out far beyond the hospital beds to a community where parents have held children with racing hearts, where local police face mounting questions about how quickly they acted to stop the shooter and where mental health experts say the scars of trauma will be indelibly etched.

“They are holding onto this terrible, horrific memory,” said Dr. Amanda Wetegrove-Romine, a San Antonio psychologist who attended high school in Uvalde and assisted in community counseling services in the days after the May 24 shooting.

Children were having nightmares and clinging to their parents, she said.

One third-grader, 8-year-old Jeremiah Lennon, feared he would be killed if he went back to school after surviving the shooting in a classroom next to the room where three of his friends were slain. He was changed by the shooting, his grandmother Brenda Morales said, now sitting quietly, not eating much and just staring into space.

“He’s changed. Everything’s changed," she said.

As Erika Santiago attended the funeral this week for 10-year-old Amerie Jo Garza, she recounted how her 10-year-old son, Adriel, watched in horror when the first images came out on the news and he recognized two of his friends from kindergarten: Amerie and Maite Rodriguez.

Although the Santiago family has moved and now lives in San Antonio, Adriel did not want to go back to his school: “He told me, “Mom, I just don’t feel safe.’”

Mental health experts said that because most of the victims were children, trauma can have a particularly long-lasting impact.

“They are in an important stage of development. Their worldview is forming and they are learning whether the world is safe or unsafe,” said Dr. Arash Javanbakht, who directs the Stress, Trauma, and Anxiety Research Clinic at Wayne State University.

“Trauma stays with children the rest of their lives,” he said, adding that childhood trauma has been linked to a host of health problems later in life.

In the communities across the country shaken by school shootings over the years — Columbine High School in Colorado, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida, Santa Fe High School in Texas and Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut — trauma has manifested for years. Survivors of Columbine, now adults, spoke out in recent days to say news of the shooting reopened the wounds of their trauma.

“I spent the formative part of my career in a Connecticut elementary school. I will never forget the ripple effect of fear and heartbreak that spread among students and teachers in the aftermath of the horrific Sandy Hook shooting," U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona said in a statement Wednesday as he announced a federal program would be set up to offer mental health support in Uvalde.

Mental health experts said a range of support will be needed for the survivors, beginning with what is known as “psychological first aid” in the immediate aftermath to counseling sessions to address trauma symptoms that can last for months and even years. The ability of the community to come together to heal will also be crucial, with parents playing an important role in discussing emotions with their children.

“Support and connectedness with community members and fellow survivors can be a powerful source of resilience, collective remembering, collective healing and purpose,” said Nicole Nugent, an expert in treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder who works as a professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Wetegrove-Romine, the psychologist, said Uvalde was a “close-knit” community where “everyone is connected,” yet the intense scrutiny of the speed of the police response has also prompted a “conflicted grief.”

She worried that in the small Texas community, where mental health resources are thin and what she described as a culture of stoicism that prevails among many, people won't get help when they need it. She has begun collecting specialized journals to send to adults in Uvalde to help them process their grief.

“I worry about the long-term resources — there will likely be another shooting like this and resources will need to leave" to treat survivors of that tragedy, she said. "What happens to the people of Uvalde?”

___

Groves reported from Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Associated Press writers Jim Vertuno in Austin, Texas, and Jamie Stengle in Dallas contributed.