CHARLOTTE, N.C. — While primary elections take focus in the Carolinas, Leia Castañeda Anastacio has been closely eyeing another vote abroad.

The Philippines, by the latest counts, elected the son of an ousted dictator to the presidency. Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. had more than 31 million votes, based on the unofficial count from Monday’s elections, winning by a landslide.

"The propaganda plus the disaffection -- the results were not surprising, but still, when it actually happened, I'm like, 'Oh, my God, it's a restoration,'" Anastacio said.

For some Filipino-Americans, like Anastacio, the Marcos name stirs up strong emotions. Anastacio lives in the Charlotte area now but grew up in Manila during the regime of the only Philippine dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, the new presumptive president's late father.

"I get these post-traumatic flashbacks about what it was like to grow up under martial law," Anastacio said.

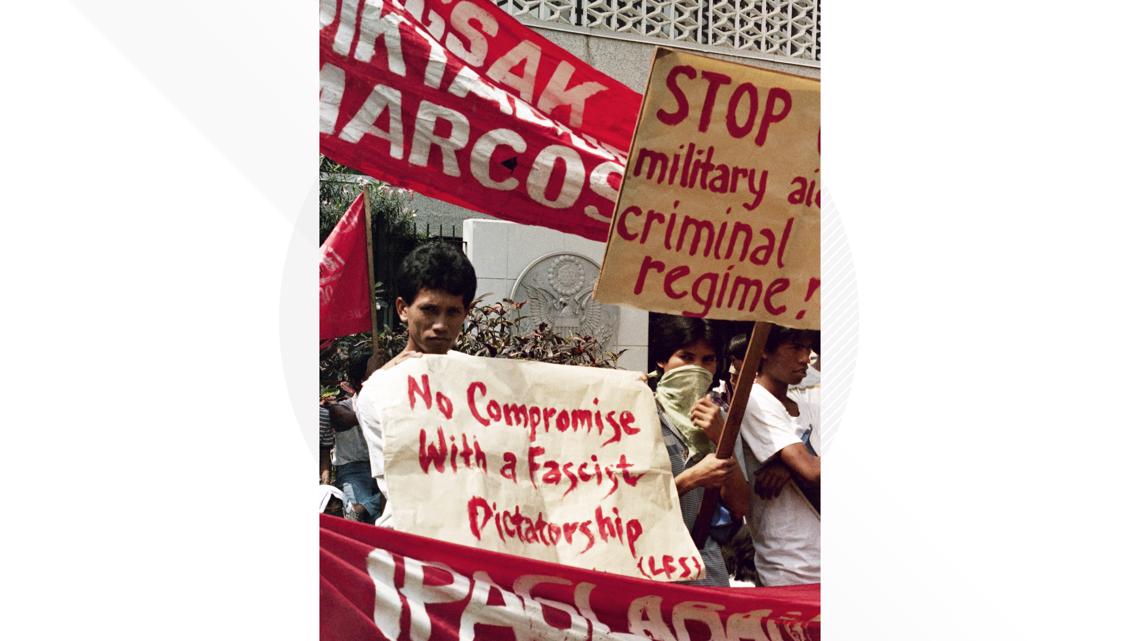

In 1972, Marcos was nearing the end of his second term as president, when historians say he declared martial law, paving the way to seizing power indefinitely. His 20-year regime was marked by corruption, human rights abuses, and the siphoning of billions of dollars from the Philippine economy.

"The image of (Imelda's) shoes, I guess, is a good metaphor for their thievery," Anastacio said.

Marcos' wife Imelda was probably best known for her lavish lifestyle and massive shoe collection, reportedly totaling 3,000 pairs.

"There's also the legacy of brutality," Anastacio said.

Historians say that brutality included political murders, and in 1983, the assassination of Marcos's longtime political opponent, Benigno Aquino, Jr.

"There's that sense of vulnerability that, if he could kill somebody, or if he could have somebody killed, so high-profile, nobody was safe," Anastacio said.

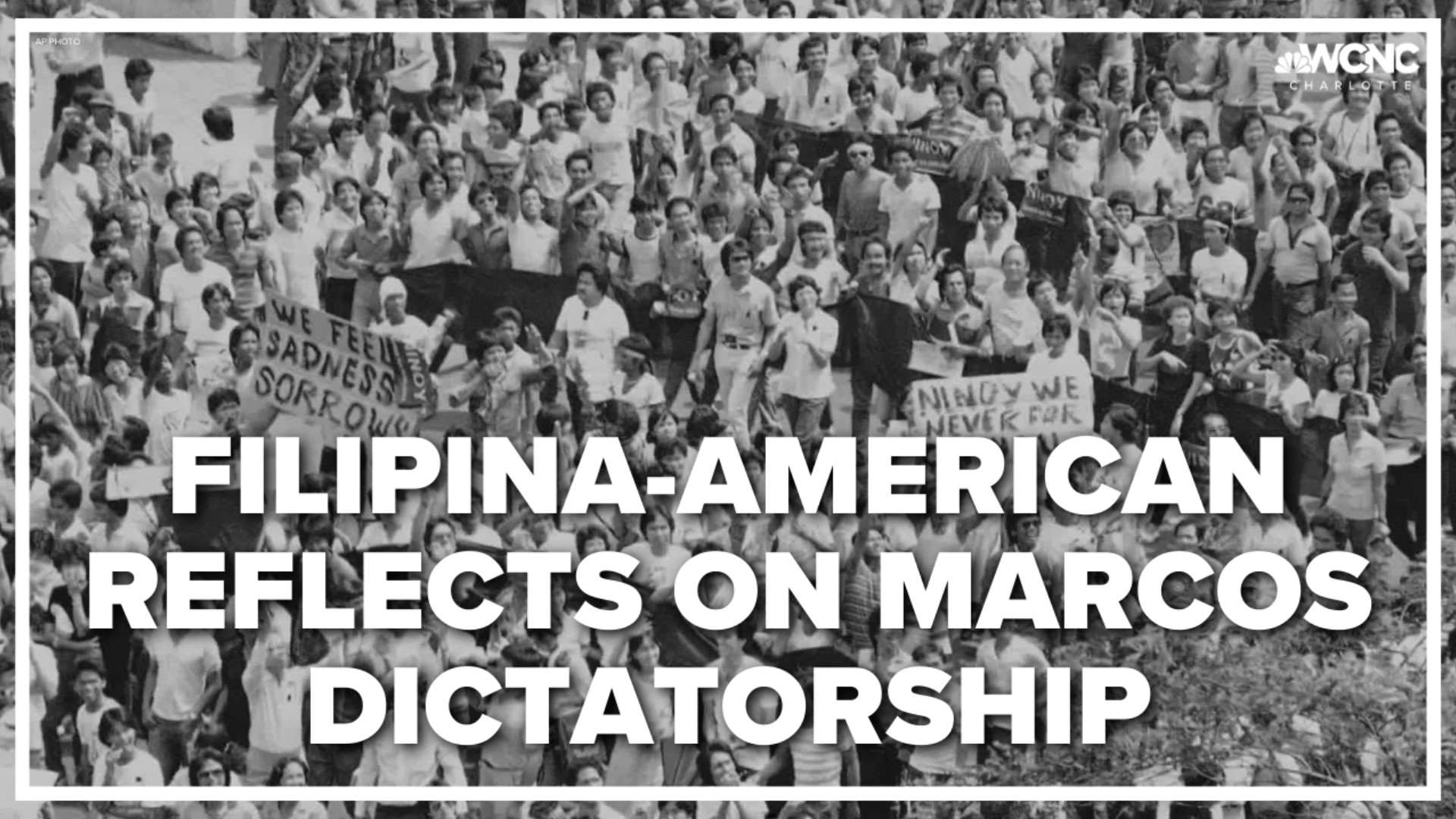

Anastacio and countless others took to the streets in the years that followed--protests culminating in the "People Power" movement in Feb. 1986, which ousted the Marcos family from power, driving them from the country. They fled to Hawaii.

"If anybody had told me then that they would be back in 36 years, I wouldn't have believed them because it was such a heavy time," Anastacio said. "Everybody was just so hopeful."

Investigative journalism points to social media disinformation, softening the Marcos image to the younger generation, as one reason for the family's rise to power again. Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. denies such tactics.

However, Anastacio said the "mythmaking" about the Marcos regime was also bolstered by true voter disillusionment with prior governance.

"Maybe if there was a sense that... the results were good in governing then maybe the propaganda would not have stuck," Anastacio said. "They would not have found as receptive an audience."

After extensively researching the origins of the constitution in the Philippines, which she details in her book The Foundations of the Modern Philippine State, Anastacio has theories on how the current governmental system might allow for greater abuse of power, including dictatorships.

"We got the U.S. constitutional experience during the Progressive Era here," Anastacio said. "There was this sense that there was so much capacity for good that government could do. So, the sense was to unleash that power ... You can use that for good or bad, and obviously, when people know how to work that system, you can use it for all kinds of things, including that."

Hear Anastacio's explanation of the governmental system in the Philippines and the historic nature of this election.

Contact Vanessa Ruffes at vruffes@wcnc.com and follow her on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.