CHARLOTTE, N.C. — While getting a large percentage of the country on board with a COVID-19 vaccine appears to be the next big task for health officials, many are still dealing with one of their first assignments: gaining mask compliance.

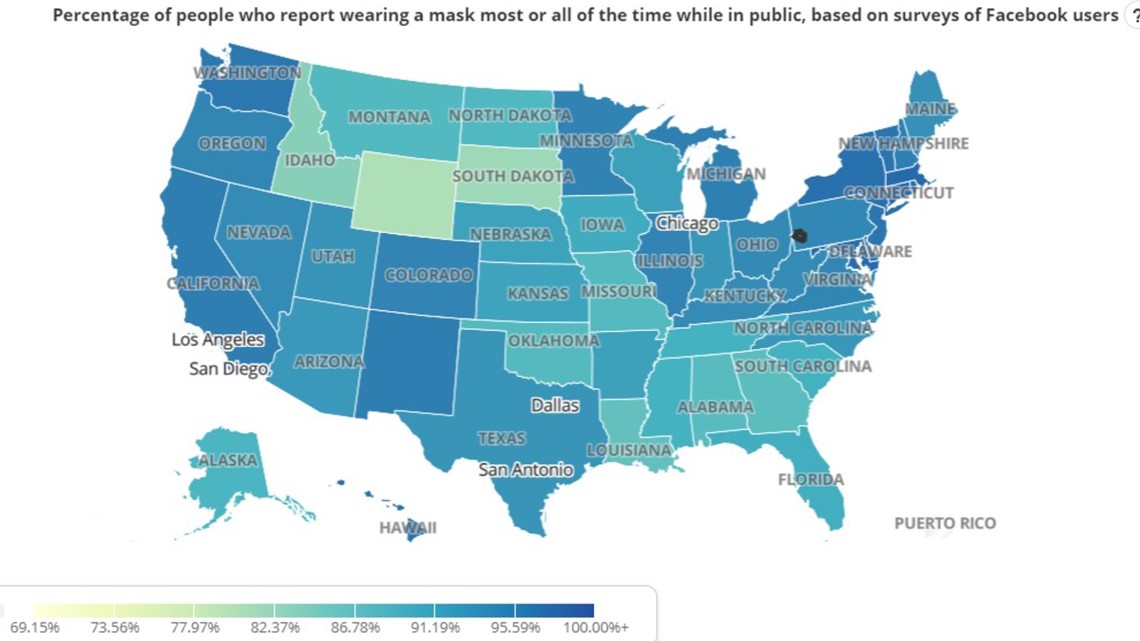

According to covidexitstrategy.org, a group of public health and crisis experts, mask compliance in the states and D.C. ranges from 81% to 99%. While that seems like a passing grade, health officials have said it takes everyone masking up for the most effective slowing of the virus.

The database shows North Carolina with 91% mask compliance, which ranks in the middle compared to other states. South Carolina's compliance is closer to the bottom-quarter states at 89%.

So why, after months of doctors hammering home the message that masks can save lives, are some not listening?

For Dan Ariely, a professor of Behavioral Economics at Duke University, the answer comes down to the "it won't happen to me" effect that gets continually reinforced through experiences.

"Think about something like texting and driving," said Ariely. "If you think to yourself: the probability of texting and driving and something bad happening is 1%. So, one day you drive and you’re tempted by your phone, and you text, and nothing happened. So, you update your belief and say, 'Maybe it’s not 1%. It’s more like three-quarters of a percent.'"

In pandemic terms, essentially, it's an optimism bias that gets stronger every time a person goes out, doesn't mask up and doesn't get sick or knowingly realize they've infected another.

"If you, one day, walk without a mask, or you're not careful, and nothing bad happens to you, you learn the wrong lesson," Ariely said. "You learn it again, and again and again until it is too late."

Gary Bennett, a Duke University professor of Psychology and Neuroscience, also cautions that lecturing, coercing, or even trying to instill fear to gain compliance might not be the best route.

Surprisingly, Bennett also said more education doesn't always mean more compliance.

"It actually doesn't work for most health conditions and most public health calamities like this one," Bennett said. "We want to do a lot less telling people what to do, and show them examples of how they can do it. It really starts with leaders in organizations."

While modeling at the top is important, both Bennett and Ariely advocate for more positive reinforcement and building up masking as a social norm.

"Be really, really careful to encourage people and not to browbeat them when they have not adhered," said Bennett.

"We need social understanding that this is the right behavior," said Ariely. "We need people to say to each other, 'Thank you for wearing your mask' or 'I'm sorry. I don't feel comfortable. Would you mind putting a mask on?' It has to be friendly enforcement."